Supplemental Videos

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

In the previous section, we introduced periodic functions and demonstrated how they can be used to model real life phenomena like the rotation of the London Eye. In fact, there is an intuitive connection between periodic functions and the rotation of a circle. In this section, we will use our intuition and formalize this connection by exploring the unit circle and its unique features that lead us into the rich world of trigonometry.

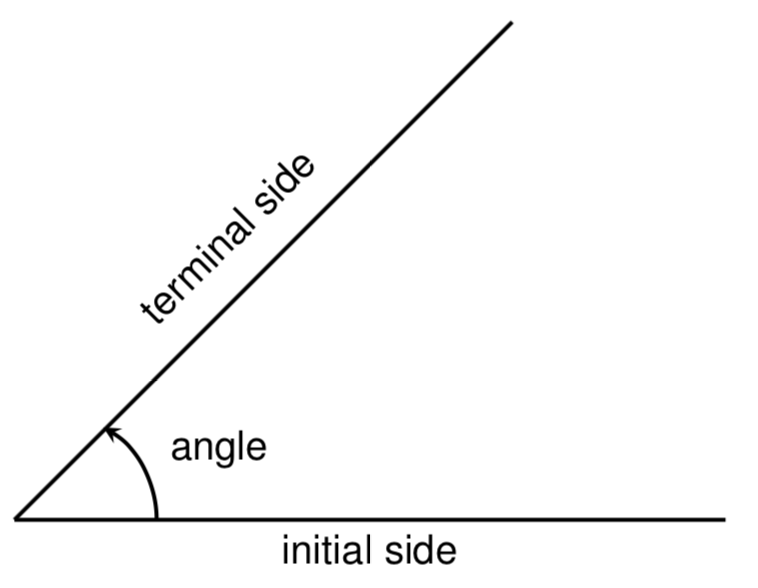

Many applications involving circles also involve a rotation of the circle so we must first introduce a measure for the rotation, or angle, between two rays (line segments) emanating from the center of a circle.

The measure of an angle is a measurement between two intersecting lines, line segments, or rays, starting at the initial side and ending at the terminal side. It is a rotational measure, not a linear measure.

When measuring angles on a circle, unless otherwise directed, we measure angles in standard position: starting at the positive horizontal axis with a counterclockwise rotation.

A degree is a unit of measurement of an angle. One rotation around a circle is equal to 360 degrees.

An angle measured in degrees should always include the degree symbol \(^\circ\) or the word "degrees" after the number. For example, \(90^\circ=90\) degrees.

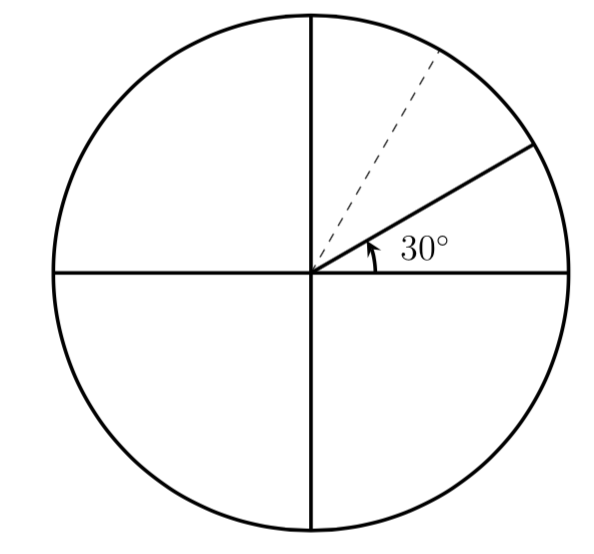

Give the degree measure of the angle shown on the circle.

The vertical and horizontal lines divide the circle into quarters. Since one full rotation is 360 degrees, each quarter rotation is \(360^\circ / 4 = 90^\circ\text{.}\)

Draw an angle of \(30^\circ\) on a circle.

An angle of \(30^\circ\) is \(1/3\) of \(90^\circ\) so by dividing a quarter rotation into thirds, we can draw a line showing an angle of \(30^\circ\text{.}\)

When representing angles using variables, it is traditional to use Greek letters. Here is a list of commonly encountered Greek letters.

| \(\theta\) | \(\phi \hspace{.075in} \text{or} \hspace{.075in} \varphi\) | \(\alpha\) | \(\beta\) | \(\gamma\) |

| theta | phi | alpha | beta | gamma |

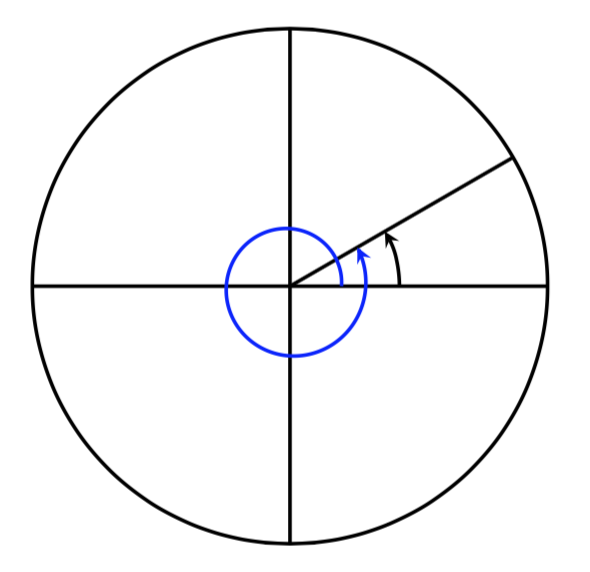

Notice that since there are 360 degrees in one rotation, an angle greater than 360 degrees would indicate more than one full rotation. Shown on a circle, the resulting direction in which this angle's terminal side points is the same as another for an angle between 0 and 360. These angles are called coterminal.

After completing their full rotation based on the given angle, two angles are coterminal if they terminate in the same position, so their terminal sides coincide (point in the same direction).

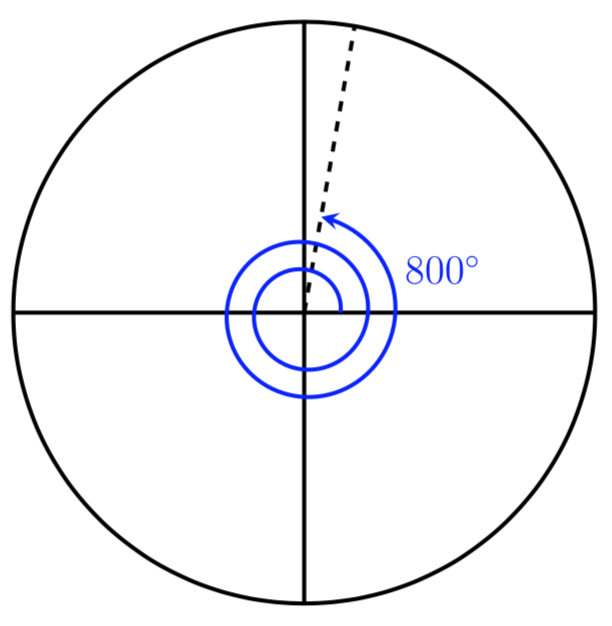

Find an angle \(\theta\) that is coterminal with \(800^\circ\) where \(0^\circ \leq \theta \lt 360^\circ \text{.}\)

Since adding or subtracting a full rotation, or 360 degrees, would result in an angle with the terminal side pointing in the same direction, we can find coterminal angles by adding or subtracting 360 degrees.

An angle of 800 degrees is coterminal with an angle of

It is also coterminal with an angle of

Finding the coterminal angle between 0 and \(360^\circ\) can make it easier to see which direction the terminal side of an angle points in.

Find an angle \(\alpha\) that is coterminal with \(870^\circ\) where \(0^\circ \leq \alpha \lt 360^\circ \text{.}\)

To find angles with the terminal sides pointing in the same direction, we can subtract 360 degrees:

Therefore \(870\) degrees is coterminal with \(150\) degrees.

On a number line, a positive number is measured to the right and a negative number is measured in the opposite direction (to the left). Similarly, a positive angle is measured counterclockwise and a negative angle is measured in the opposite direction (clockwise).

Draw an angle of \(-45^\circ\) on a circle and find a positive coterminal angle \(\alpha\) where \(0^\circ \leq \alpha \lt 360^\circ \text{.}\)

Since 45 degrees is half of 90 degrees, we can start at the positive horizontal axis and measure clockwise half of a 90 degree angle.

We can find a positive coterminal angle by adding 360 degrees.

Find an angle \(\beta\) that is coterminal with \(-300^\circ\) where \(0^\circ \leq \beta \lt 360^\circ \text{.}\)

Since \(-300^\circ+360^\circ=60^\circ\text{,}\) \(60\) degrees is coterminal with \(-300^\circ\text{.}\)

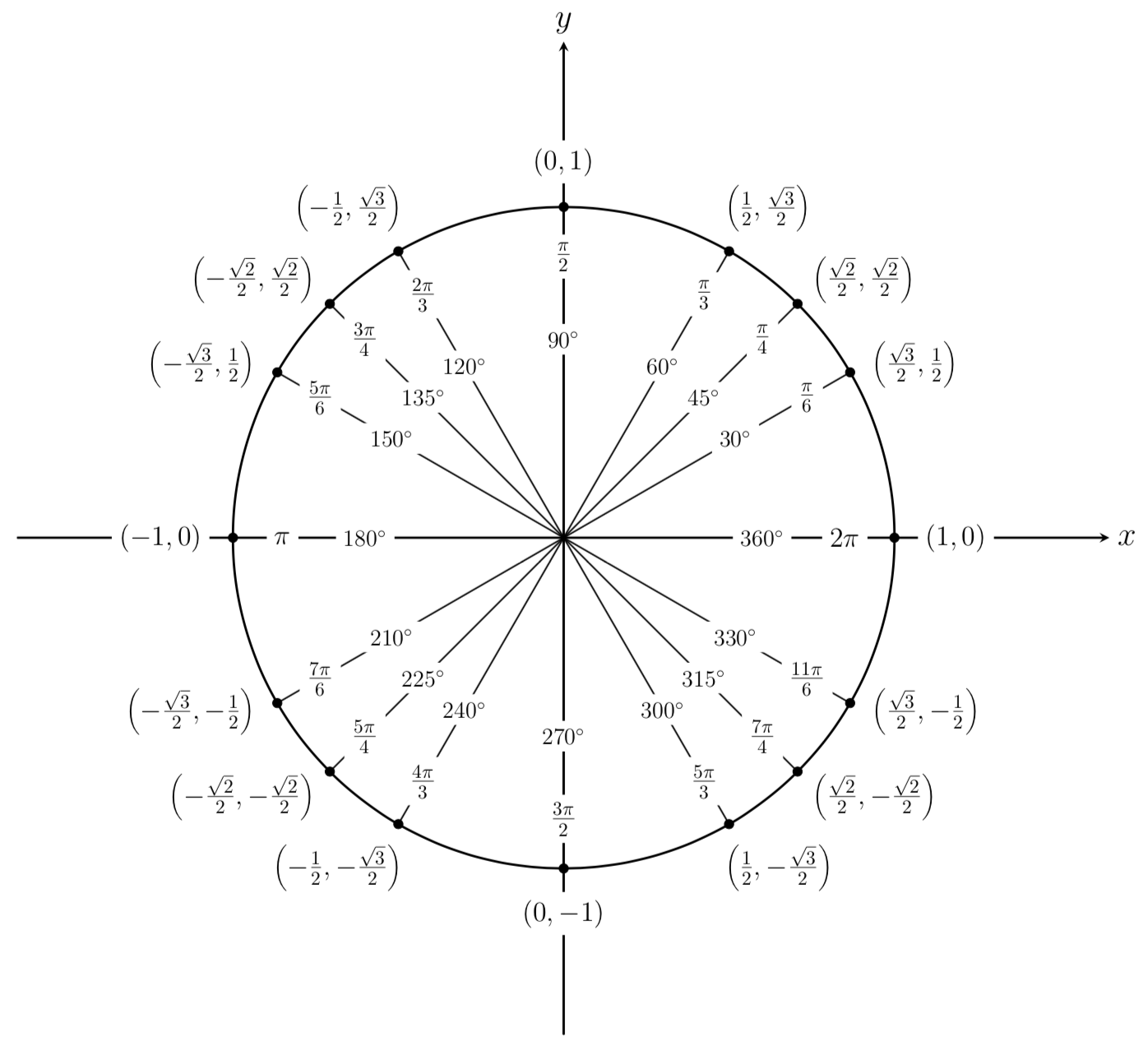

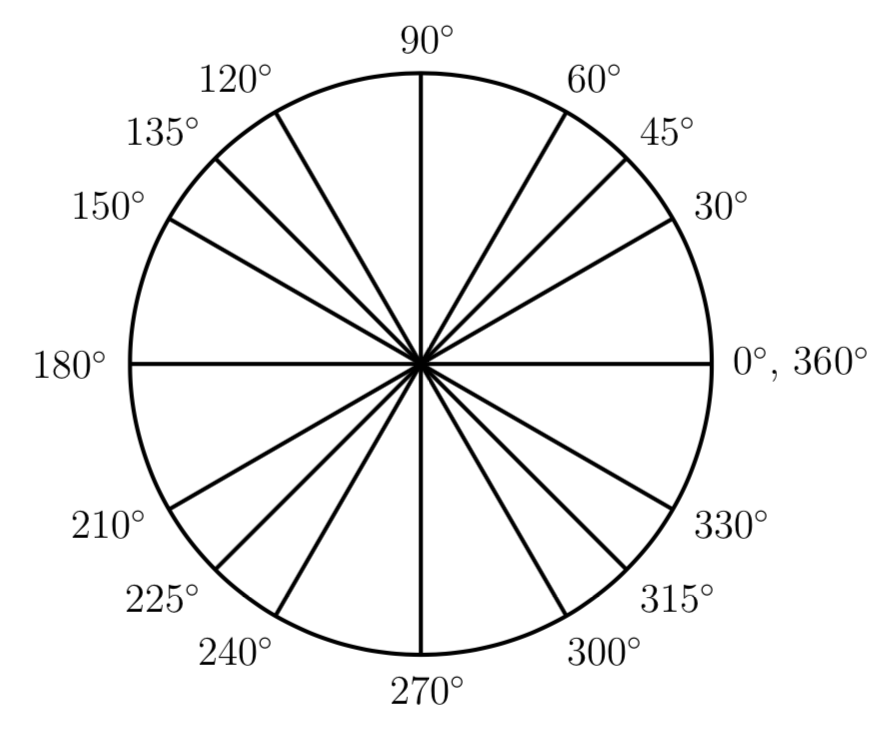

It can be helpful to know some of the frequently encountered angles in one rotation of a circle. Multiples of 30, 45, 60, and 90 degree angles are commonly encountered in many trigonometric applications. These angles are shown below. Becoming familiar with these angles and understanding how they relate to one another will be useful as we study the properties associated with them.

While measuring angles in degrees may be familiar, doing so often complicates matters since the units of measure can get in the way of calculations. For this reason, another measure of angles is commonly used. This measure is based on the distance around the unit circle.

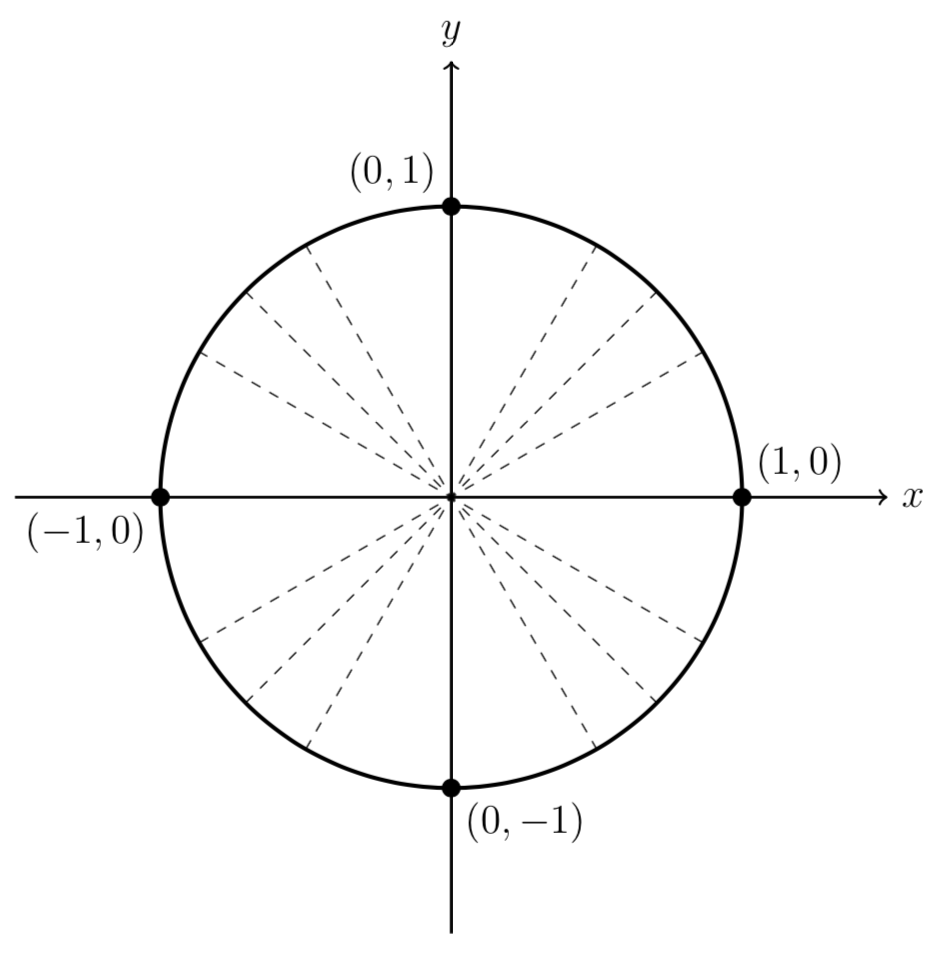

The unit circle is a circle of radius 1, centered at the origin of the \((x,y)\) plane. When measuring an angle around the unit circle, we travel in the counterclockwise direction, starting from the positive \(x\)-axis. A negative angle is measured in the opposite, or clockwise, direction. A complete trip around the unit circle amounts to a total of 360 degrees.

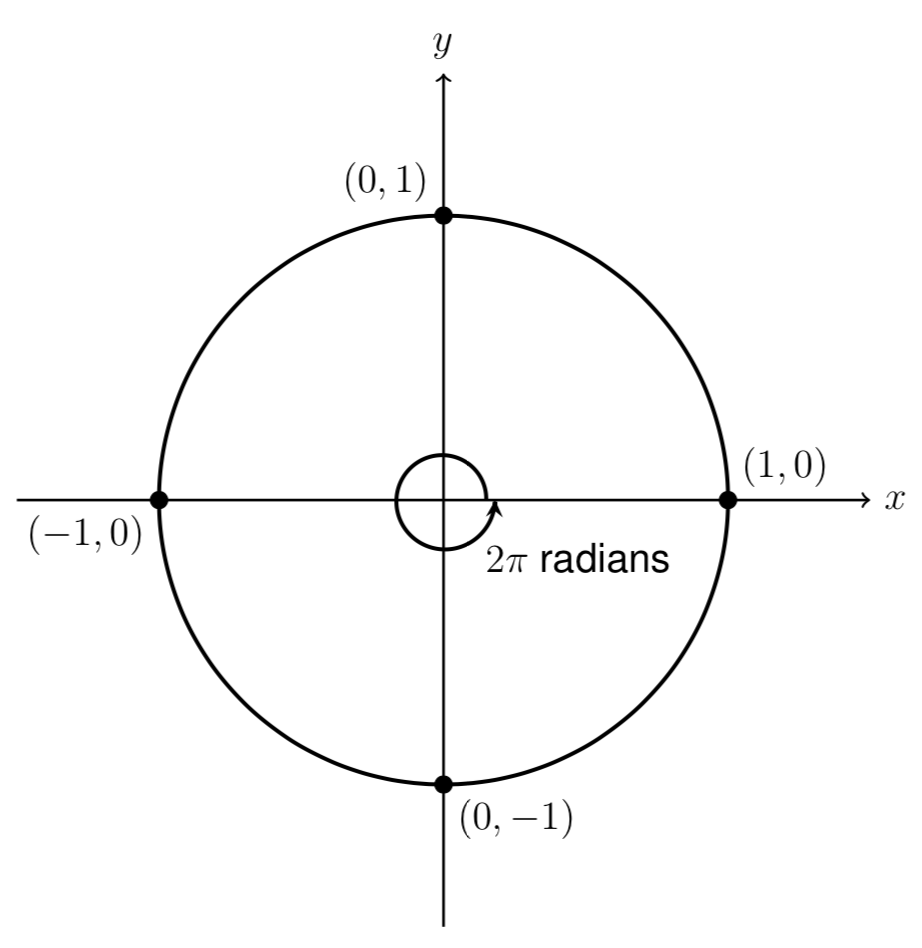

A radian is a measurement of an angle that arises from looking at angles as a fraction of the circumference of the unit circle. A complete trip around the unit circle amounts to a total of \(2\pi\) radians.

Radians are a unitless measure. Therefore, it is not necessary to write the label "radians" after a radian measure, and if you see an angle that is not labeled with "degrees" or the degree symbol, you should assume that it is a radian measure.

Radians and degrees both measure angles. Thus, it is possible to convert between the two. Since one rotation around the unit circle equals 360 degrees or \(2\pi\) radians, we can use this as a conversion factor.

Since \(360 \text{ degrees} = 2\pi \text{ radians}\text{,}\) we can divide each side by 360 and conclude that

So, to convert from degrees to radians, we can multiply by \(\displaystyle \ \frac{\pi \text{ radians}}{180^\circ}\)

Similarly, we can conclude that

So, to convert from radians to degrees, we can multiply by \(\displaystyle \ \frac{180^\circ}{\pi \text{ radians}}\)

Convert \(\displaystyle \frac{\pi}{6}\) radians to degrees.

Since we are given an angle in radians and we want to convert it to degrees, we multiply the angle by \(180^\circ\) and then divide by \(\pi\) radians.

Convert \(15^\circ\) to radians.

In this example, we start with an angle in degrees and want to convert it to radians. We multiply by \(\pi\) and divide by \(180^\circ\) so that the units of degrees cancel and we are left with the unitless measure of radians.

Convert \(\displaystyle \frac{7\pi}{10}\) radians to degrees.

Since we are given an angle in radians and we want to convert it to degrees, we multiply by the angle \(180^\circ\) and then divide by \(\pi\) radians.

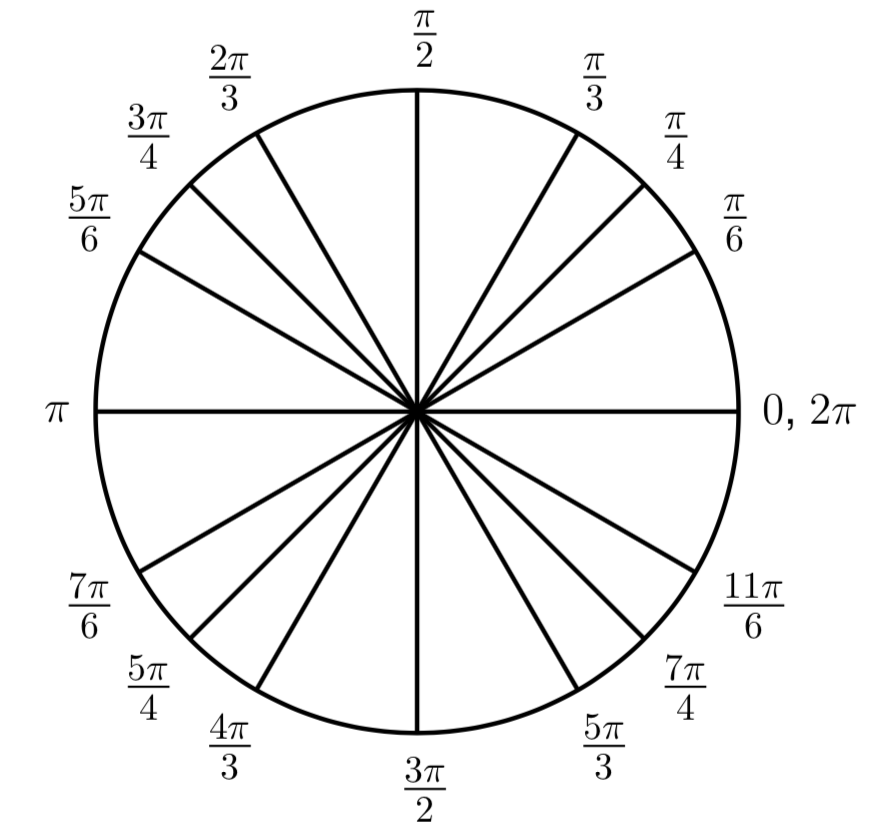

Just as we listed some frequently encountered angles in degrees on a circle, we should also list the corresponding radian values for the common measures of a circle corresponding to degree multiples of 30, 45, 60, and 90 degrees. As with the degree measurements, it would be helpful to become familiar with these angles in radians and understand how they relate to one another.

Above, we explored how to find coterminal angles for angles greater than 360 degrees and less than 0 degrees. Similarly, we can find coterminal angles for angles greater than \(2\pi\) radians and less than 0 radians.

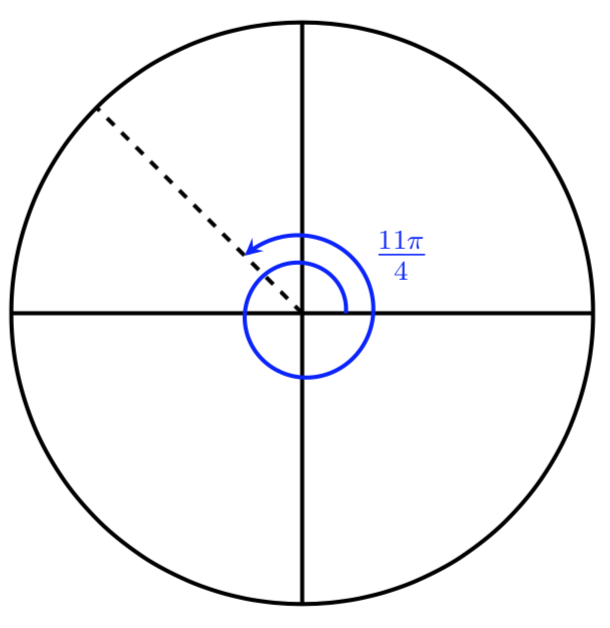

Find an angle \(\beta\) that is coterminal with \(\displaystyle \frac{11\pi}{4}\) where \(0^\circ \leq \beta \lt 2\pi \text{.}\)

When working in degrees, we found coterminal angles by adding or subtracting 360 degrees, a full rotation. Likewise, in radians, we can find coterminal angles by adding or subtracting full rotations of \(2\pi\) radians.

An angle of \(11\pi/4\) is coterminal with an angle of

Find an angle \(\phi\) that is coterminal with \(\displaystyle -\frac{11\pi}{6}\) where \(0^\circ \leq \phi \lt 2\pi \text{.}\)

An angle of \(-\frac{11\pi}{6}\) is coterminal with an angle of

While it is convenient to describe the location of a point on the unit circle using an angle, relating this angle to the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates of the corresponding point is an important application of trigonometry. To do this, we will need to apply our knowledge of triangles.

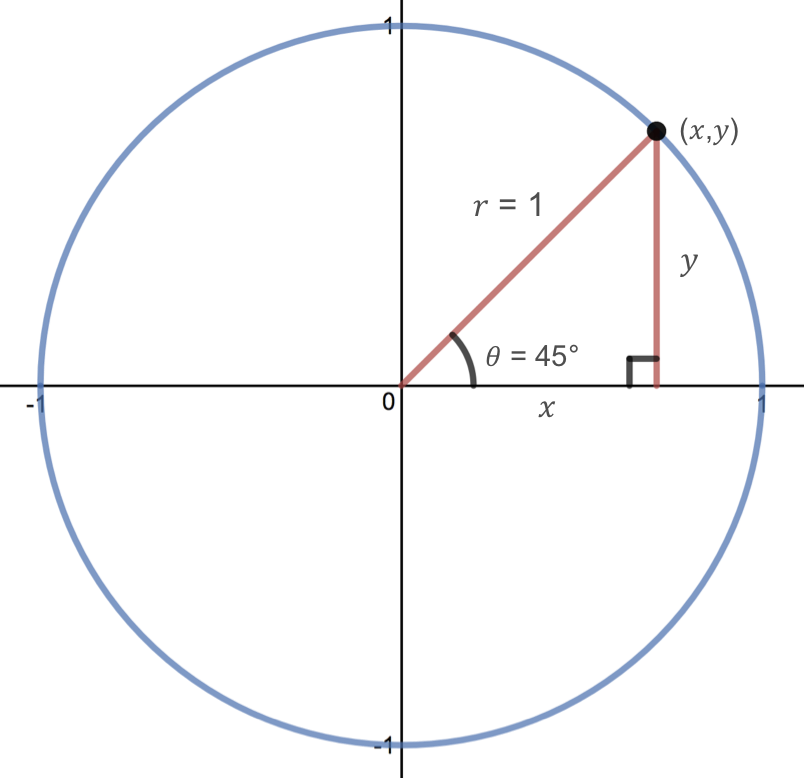

Find the \((x,y)\) coordinates for the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 45 degrees or \(\pi/4\) radians.

Let's start by drawing a picture and labeling the known information.

We want to find the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates of the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 45 degrees or \(\pi/4\text{.}\) To do this, we can draw a vertical line from the point down to the \(x\)-axis, which forms a right triangle. The hypotenuse of this triangle is 1, since it corresponds to the radius of the unit circle, and the side lengths of this triangle are equal to \(x\) and \(y\text{.}\)

Now, using the Pythagorean Theorem, we get that

Since the triangle formed is a 45-45-90 degree triangle, side lengths \(x\) and \(y\) must be equal. Therefore, we can substitute in \(x=y\) into the above equation.

Often this value is written with a rationalized denominator. Remember that to rationalize the denominator, we multiply by a term equivalent to 1 to get rid of the radical in the denominator, so

and since \(x\) and \(y\) are equal, \(\displaystyle y=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\text{.}\)

Thus, the \((x,y)\) coordinates for the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 45 degrees or \(\pi/4\) radians are

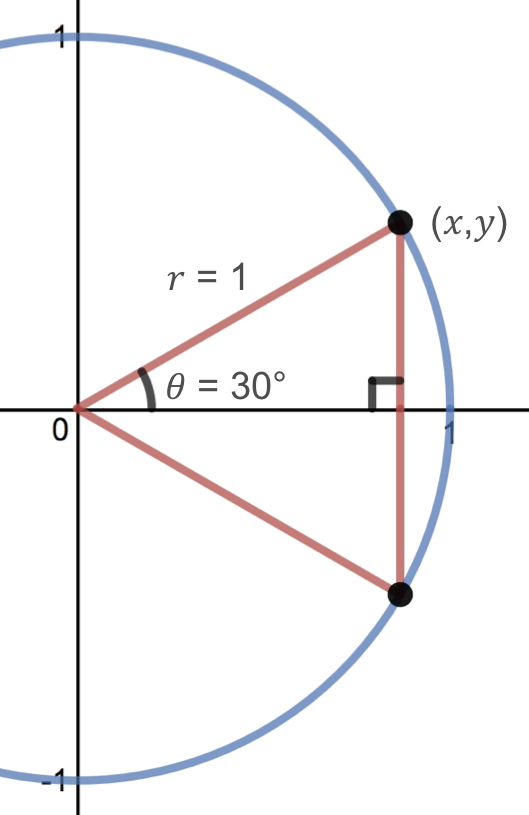

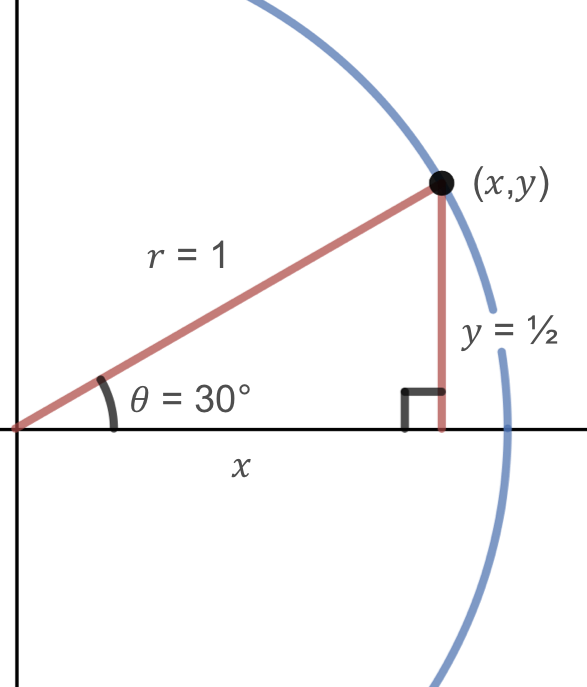

Find the \((x,y)\) coordinates for the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 30 degrees or \(\pi/6\) radians.

Let's start by drawing a picture and labeling the known information.

We want to find the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates of the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 30 degrees or \(\pi/6\text{.}\) To do this, we can draw a triangle inside the unit circle with one side at an angle of 30 degrees and another at an angle of \(-30\) degrees.

Notice that if we combine the resulting two right triangles to form one large triangle, then all three angles of the larger triangle are equal to 60 degrees.

Since all of the angles in this triangle are equal, the sides will all be equal as well. Two of the side lengths of this triangle are equal to 1 because they correspond to the radius of the unit circle. Thus, the other side length must also be equal to 1. This side also has a length of \(2y\text{.}\) Therefore, we can conclude that \(2y = 1\) so

Now, we can apply the Pythagorean Theorem to one of the right triangles to find the \(x\) value. We get that

Thus, the \((x,y)\) coordinates for the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 30 degrees or \(\pi/6\) are

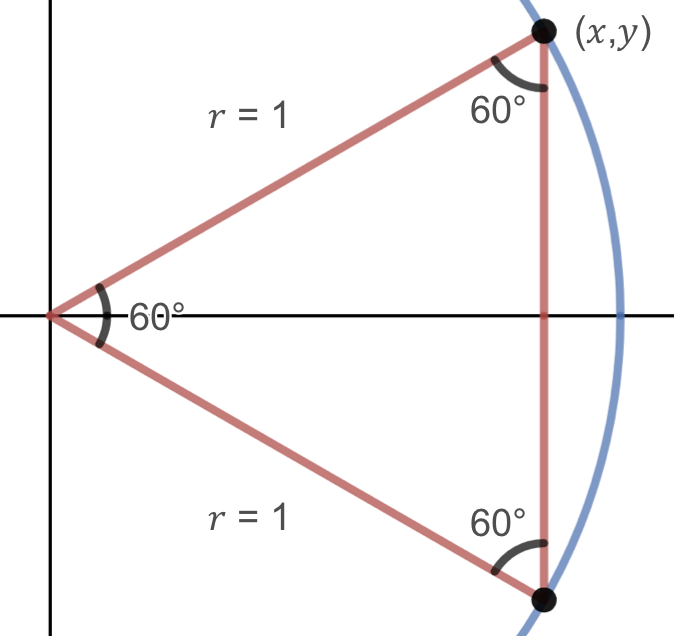

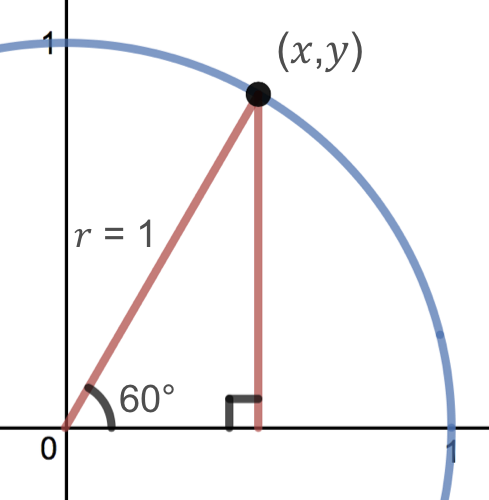

In the previous example, we applied our knowledge of triangles to find the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates of the point on the unit circle corresponding to 30 degrees. We can now use symmetry to find the \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates corresponding to an angle of 60 degrees or \(\pi/3\text{.}\) First, we draw a picture of the triangle corresponding to this point on the unit circle.

Notice that the triangle shown above is similar to the one formed by the 30 degree angle since the hypotenuse is the same length and both are 30-60-90 degree triangles. Therefore, the \((x,y)\) coordinates for 60 degrees are the same as the \((x,y)\) coordinates for 30 degrees, only switched.

Thus, the \((x,y)\) coordinates for the point on the unit circle corresponding to an angle of 60 degrees or \(\pi/3\) are

We have now found the coordinates of the points corresponding to all the commonly encountered angles in the first quadrant of the unit circle. Using symmetry, we can find the rest of the coordinates corresponding to common angles on the unit circle. A labeled picture of the unit circle is shown below.