Supplemental Videos

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

In the previous section, we determined the height of a rider on the London Eye Ferris wheel could be expressed by the equation

If we want to know the length of time during which the rider is more than 100 meters above ground, we need to know how to solve equations involving trigonometric functions. In this section, we will focus on how to solve basic trigonometric equations such as \(\sin(\theta) = \frac{1}{2}\text{.}\)

In the last chapter, we found the sine and cosine values of commonly encountered angles on the unit circle. In the examples below, we use these known values to solve for all possible solutions of a trigonometric equation.

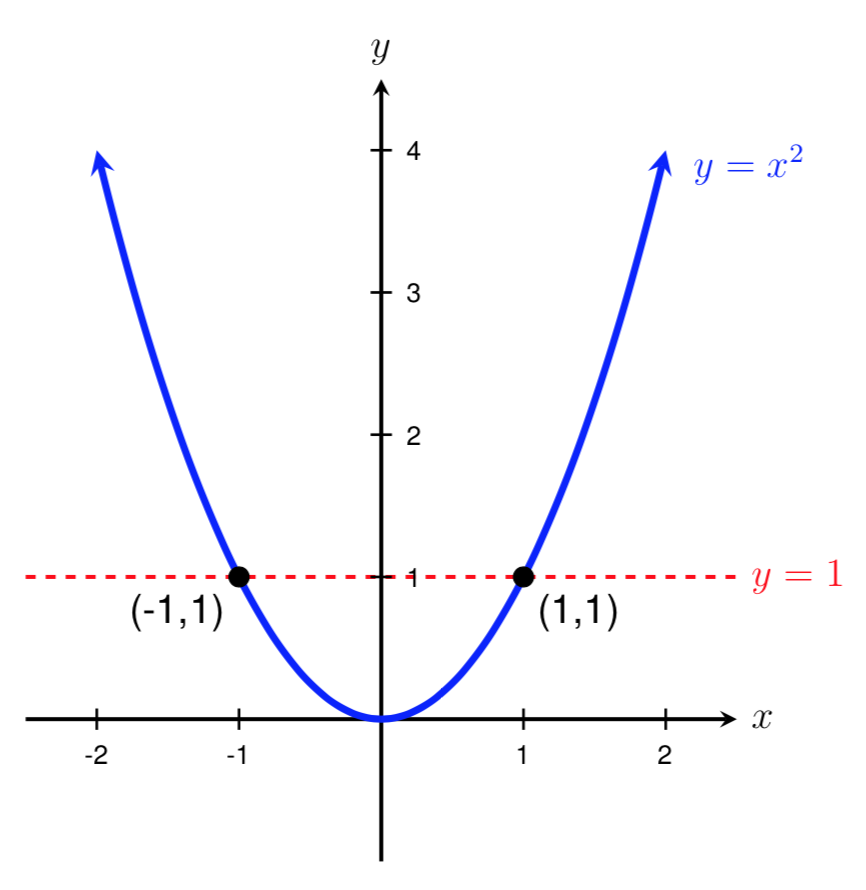

Before we discuss solving trigonometric equations, let us recall what it means to find a solution to an equation. Solutions to equations can be often be represented as the intersection points of two functions. For example, to solve the equation \(x^2 = 1\text{,}\) we could graph the functions \(y=x^2\) and \(y=1\) and find their intersection points. As shown on the graph below, there are two intersection points and thus two solutions to the equation \(x^2=1\text{:}\)

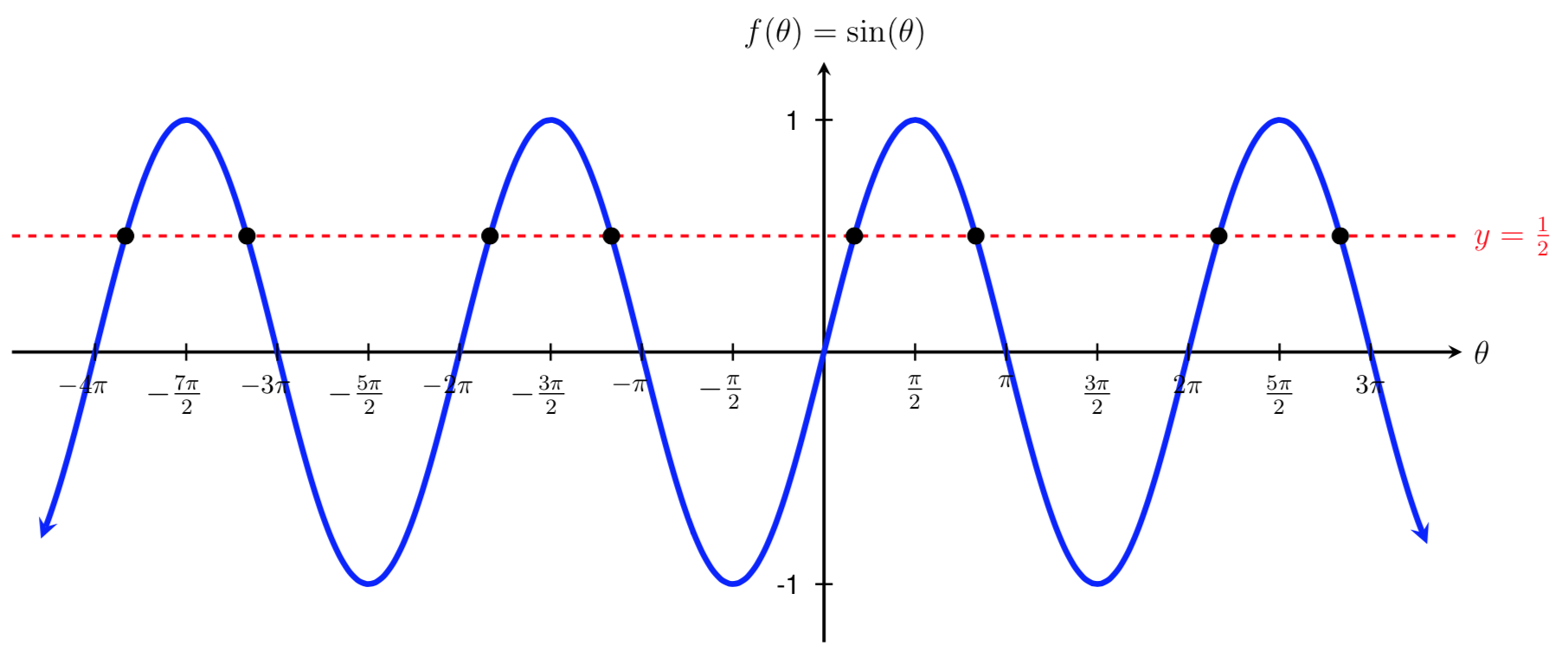

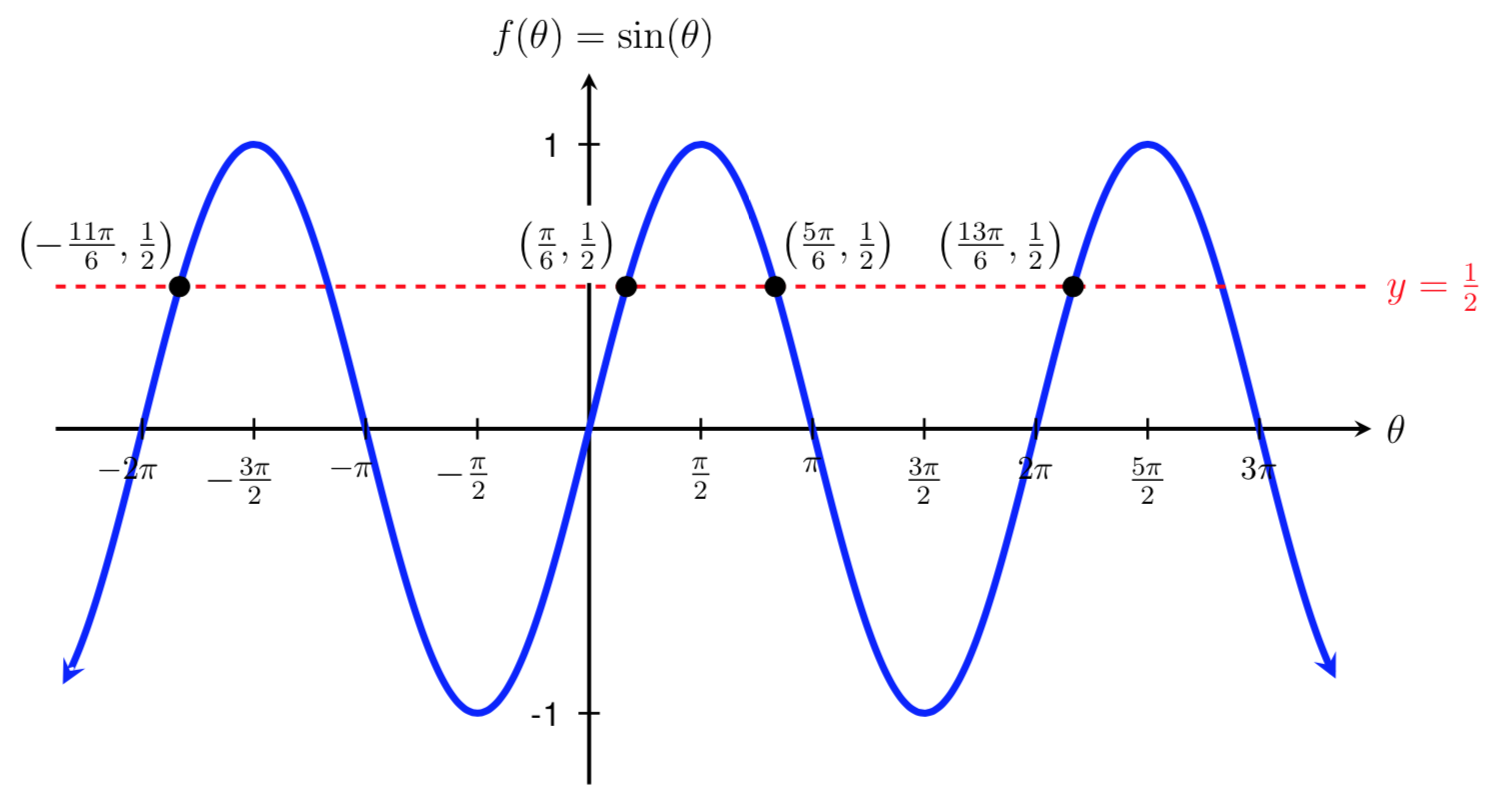

Since sine and cosine are periodic functions, equations involving these functions will often have an infinite number of solutions. For example, the solutions to the equation \(\sin(\theta) = \frac{1}{2}\) are shown below as intersection points. While only eight solutions can be seen on the graph below, there are actually an infinite number of solutions! We solve for these solutions in the following example.

Solve \(\displaystyle \sin(\theta)=\frac{1}{2}\) for all possible values of \(\theta\text{.}\)

To solve this equation, we need to identify all angles, \(\theta\text{,}\) that have a sine value of \(\frac{1}{2}\text{.}\)

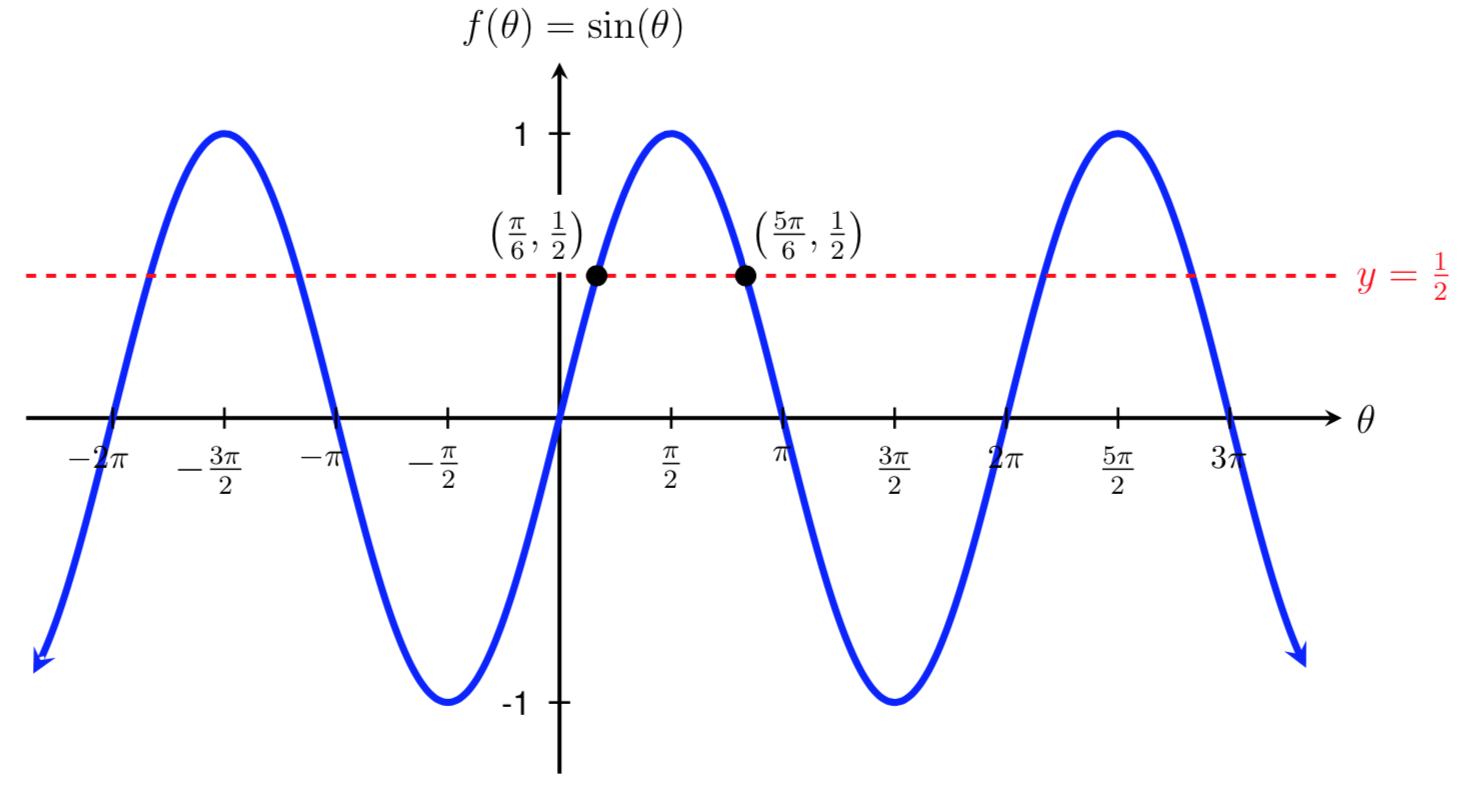

In the Inverse Trigonometric Functions Section, we found two solutions to the equation \(\sin(\theta)=\frac{1}{2}\text{,}\)

These solutions are two common angles on the unit circle that have a sine value of \(\frac{1}{2}\text{.}\)

However, if we look at the graph of \(f(\theta)=\sin(\theta)\) to see where it intersects with the horizontal line \(y=\frac{1}{2}\text{,}\) we can see that there are actually more than two solutions to the equation \(\sin(\theta)=\frac{1}{2}\text{.}\)

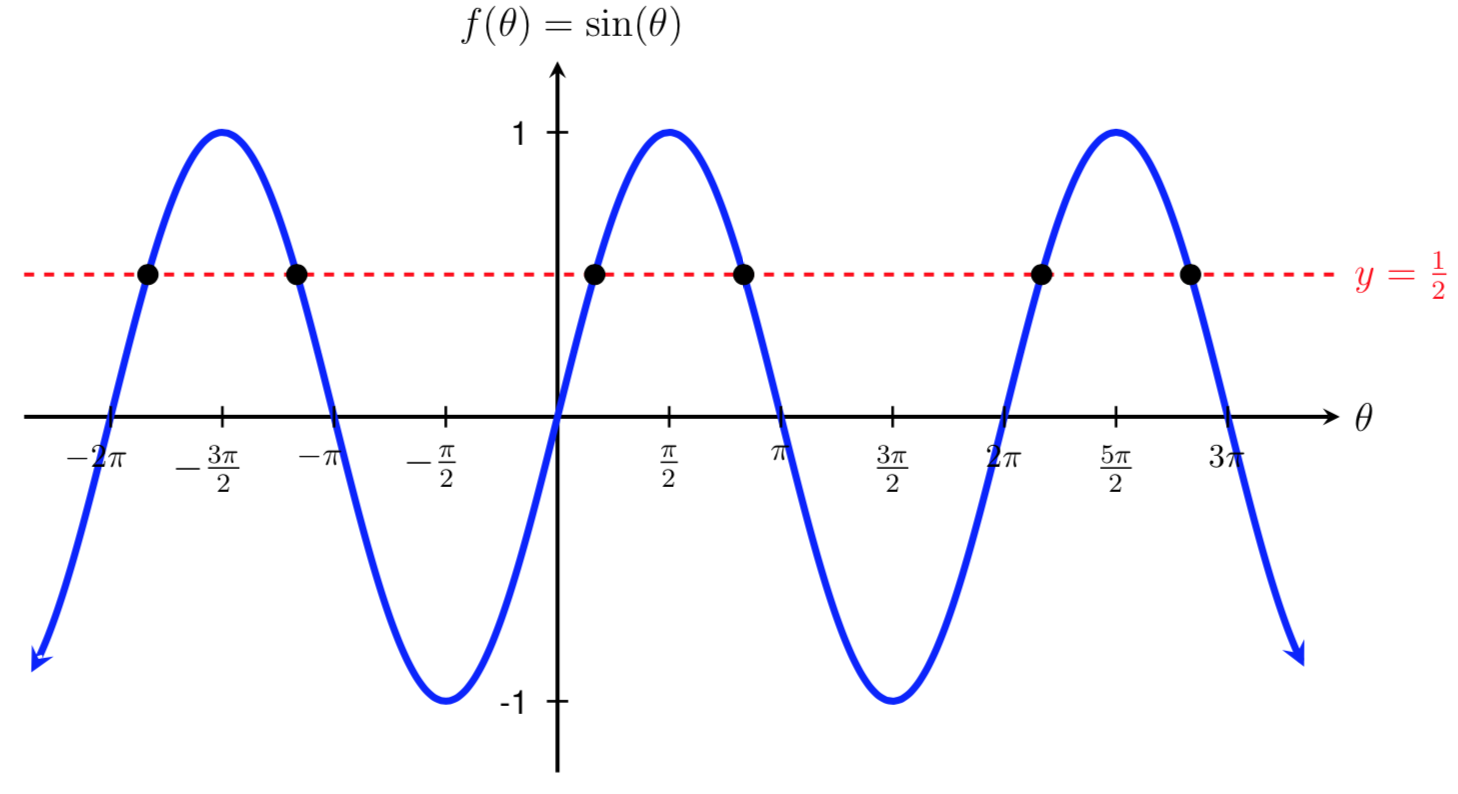

The two solutions we found above, \(\frac{\pi}{6}\) and \(\frac{5\pi}{6}\text{,}\) are shown on the graph below. We call these two angles our initial solutions (or base angles).

Because sine is a periodic function, we can use these two initial solutions to solve for all other solutions. Recall that the period of sine is \(2\pi\text{.}\) Therefore, to find another solution on the graph, we can add \(2\pi\) to \(\frac{\pi}{6}\text{:}\)

Alternatively, we could have also subtracted \(2\pi\) from \(\frac{\pi}{6}\) to give us yet another solution.

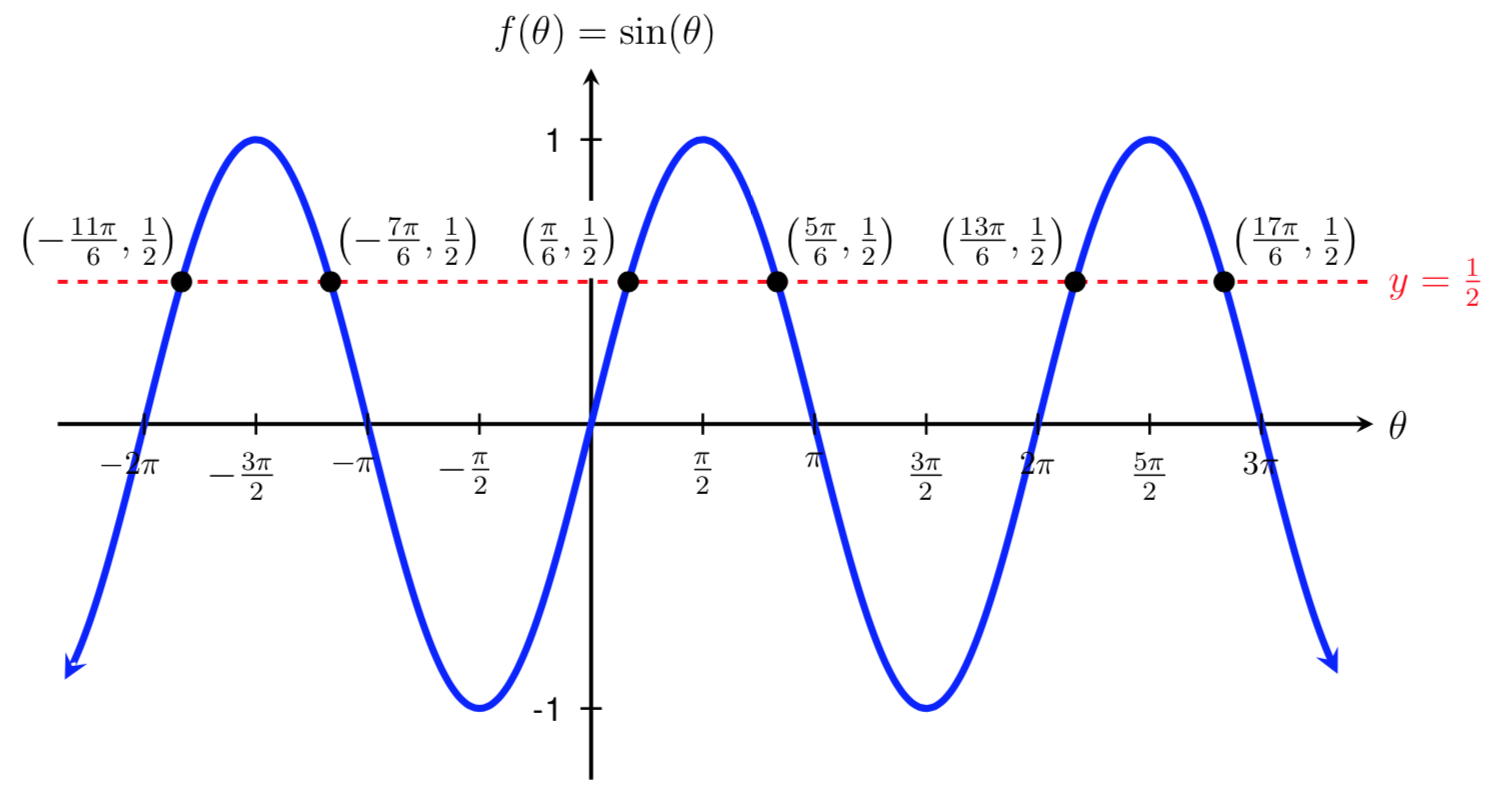

These two additional solutions are shown on the graph below.

We could also add or subtract multiples of the period for the other initial solution, \(\frac{5\pi}{6}\text{.}\) For example, if we add or substract one multiple of \(2\pi\) to \(\frac{5\pi}{6}\text{,}\) then the respective solutions are:

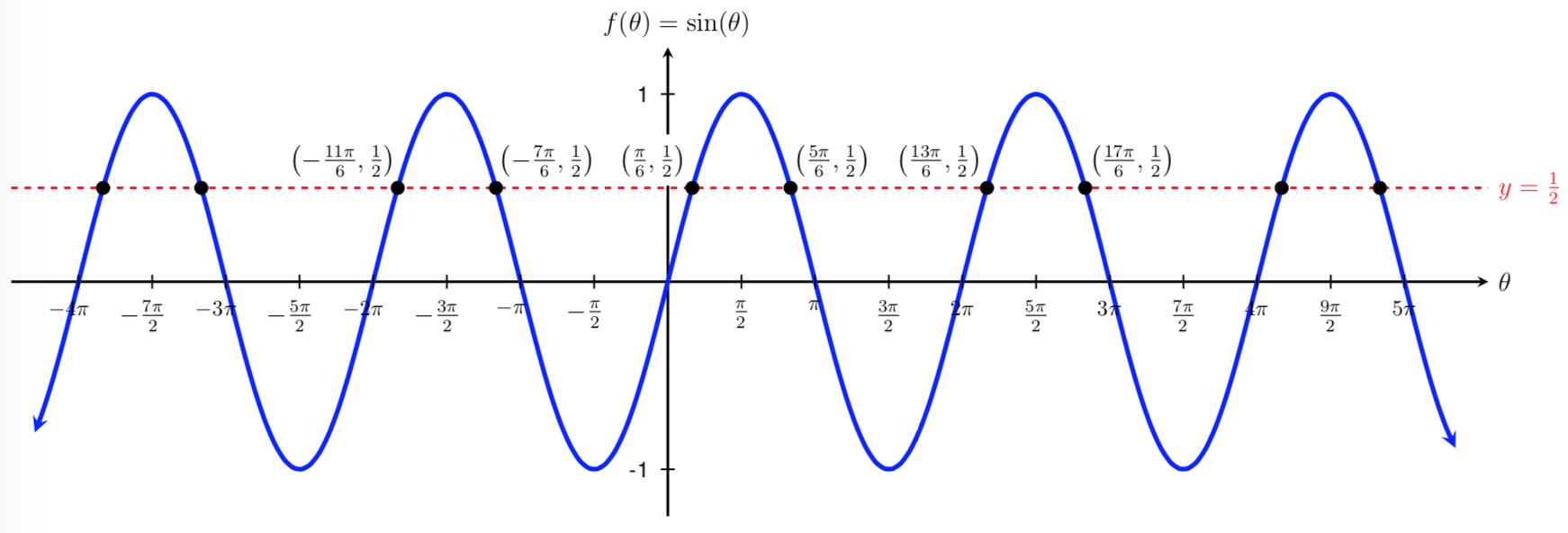

We have found all solutions shown on the graph above, but there are still infinitely many solutions left to find because the graph of sine intersects the line \(y=\frac{1}{2}\) infinitely many times.

To find all of the solutions, we add multiples of \(2\pi\) to our initial solutions. That is,

Remember that an integer is a positive or negative whole number, so \(k=..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, ...\)

We can relate these solution sets back to the intersection points on the graph above. When \(k=0\text{,}\) we get our two initial solutions:

and

When \(k=1\text{,}\) we get

and

This corresponds to the two solutions to the right of our initial solutions on the graph.

When \(k=-1\text{,}\) we get the two solutions to the left of our initial solutions: \(-\frac{11\pi}{6}\) and \(-\frac{7\pi}{6}\text{,}\) and so on.

We can also relate these solution sets to angles on the unit circle.

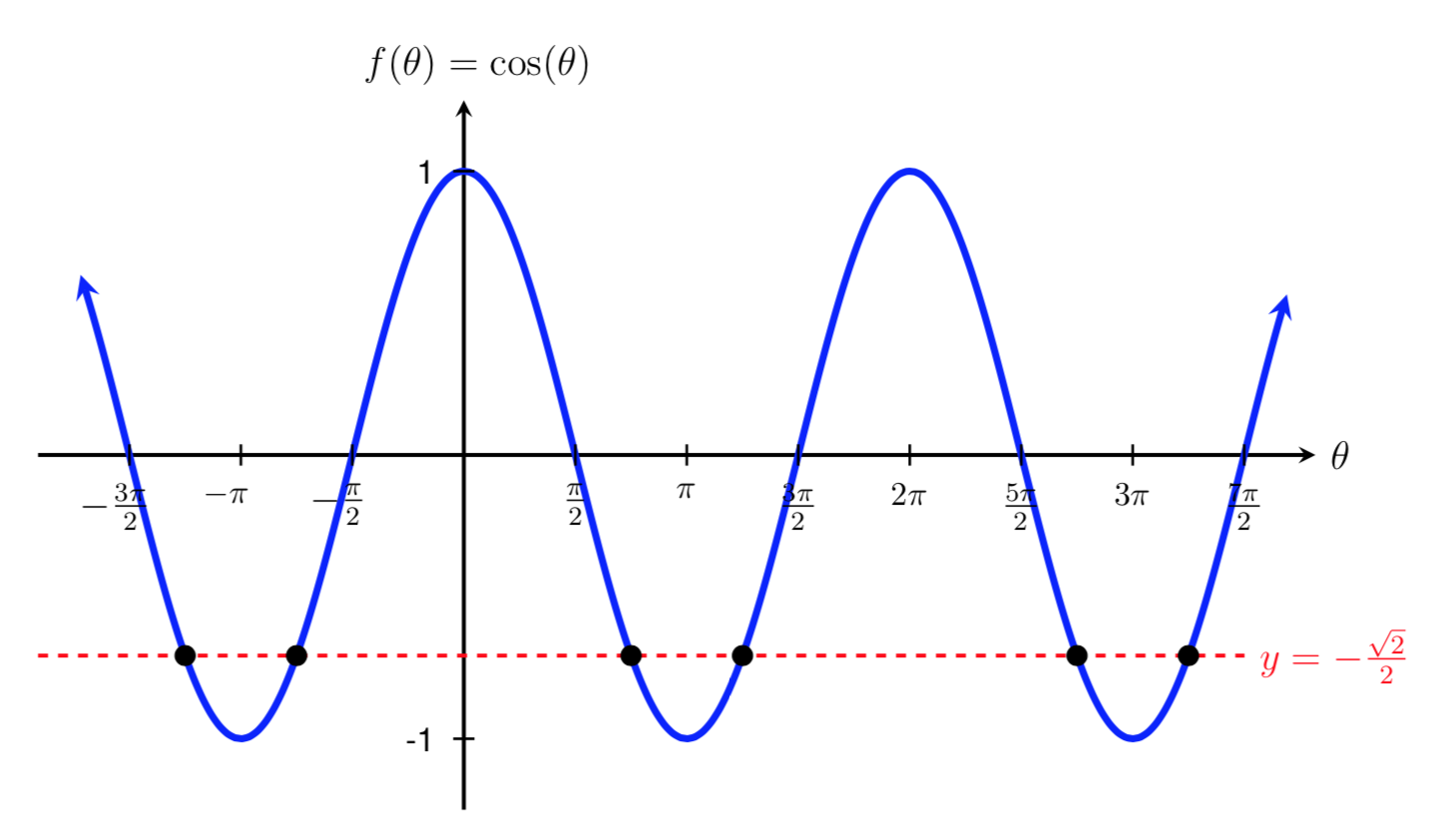

Solve \(\displaystyle \cos(\theta)=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) for all possible values of \(\theta\text{.}\)

To solve this equation, we need to identify all angles, \(\theta\text{,}\) that have a cosine value of \(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\text{.}\)

We can start by finding two initial solutions that we encountered in the last chapter. These initial solutions are two common angles between 0 and \(2\pi\) on the unit circle with a cosine value of \(-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\text{:}\)

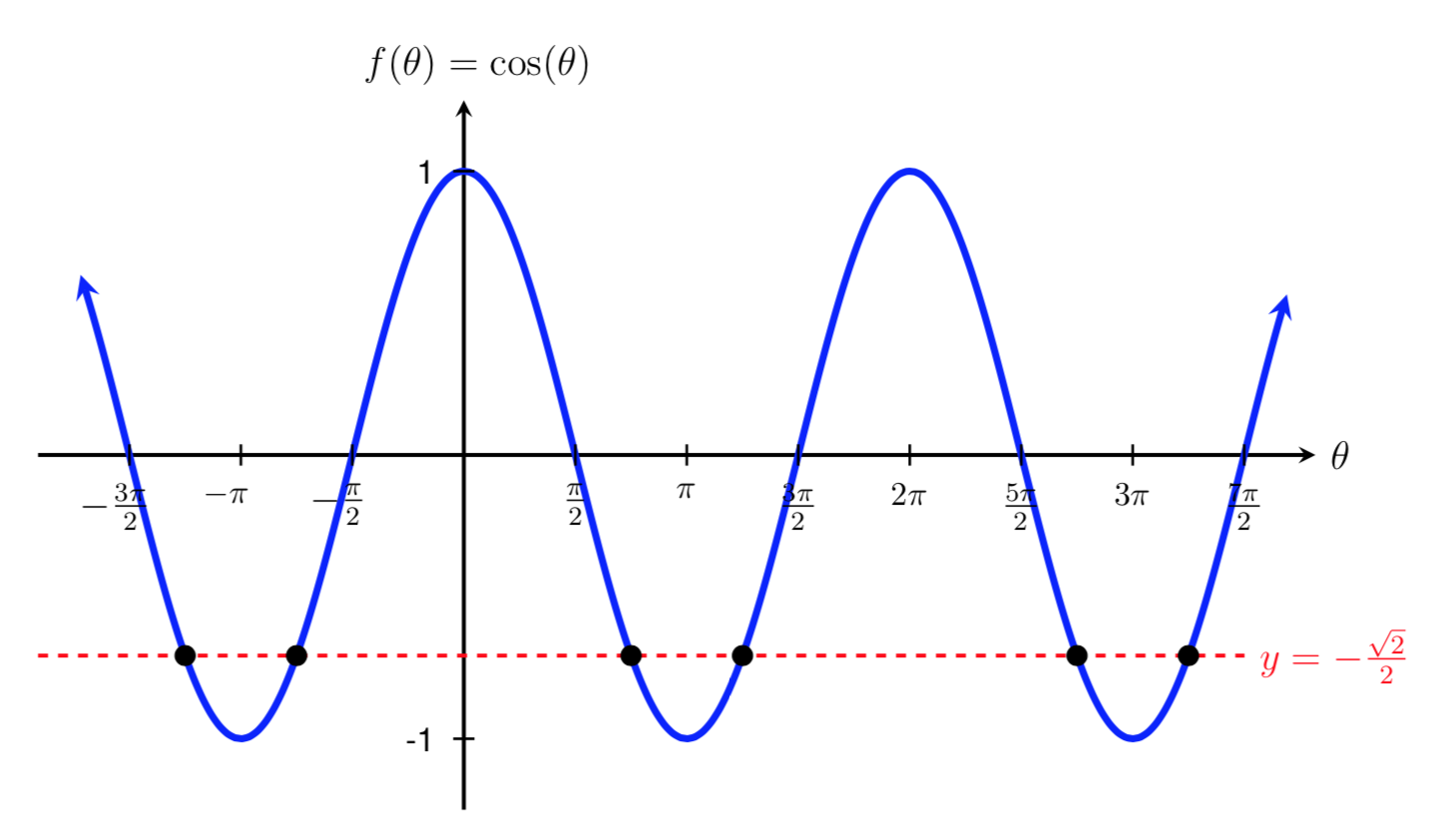

If we look at the graph of \(f(\theta)=\cos(\theta)\) to see where it intersects with the horizontal line \(y=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\text{,}\) we can see that there are an infinite number of solutions to the equation \(\cos(\theta)=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\text{.}\)

To represent the rest of the solutions we can add multiples of the period of cosine, \(2\pi\text{,}\) to our initial solutions just like we did in the last example. Therefore, the full set of solutions is

The sine and cosine functions are similar in that they both have a midline of \(y=0\text{,}\) an amplitude of 1, and a period of \(2\pi\text{.}\) The tangent function, however, has no midline or amplitude and a period of \(\pi\text{.}\) Therefore, solving equations involving tangent is slightly different than solving those involving sine or cosine.

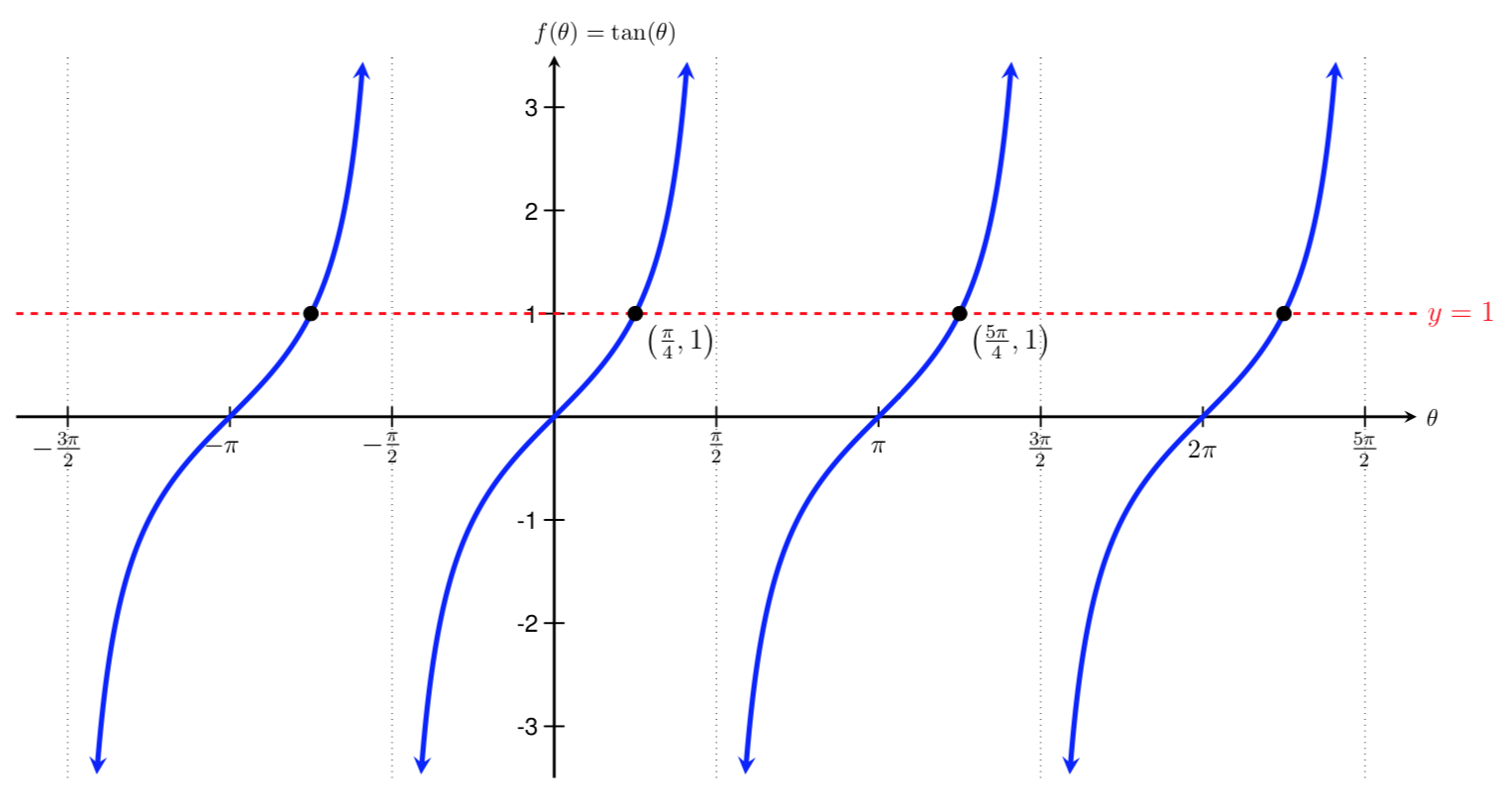

Solve \(\tan(\theta)=1\) for all possible values of \(\theta\text{.}\)

To solve this equation, we need to identify all angles, \(\theta\text{,}\) that have a tangent value of 1. We previously found two solutions to the equation \(\tan(\theta)=1\text{,}\)

These solutions are two common angles on the unit circle that have a tangent value of \(1\text{.}\) However, if we look at the graph of \(f(\theta)=\tan(\theta)\) to see where it intersects with the horizontal line \(y=1\text{,}\) we can see that there are an infinite number of solutions to the equation \(\tan(\theta)=1\text{.}\)

Notice that the two solutions we found above are \(\pi\) radians apart from one another. Because tangent is a periodic function with a period of \(\pi\text{,}\) we only need to choose one of these solutions as our initial solution. We can then use this initial solution to solve for all other solutions by adding and subtracting multiples of \(\pi\) from it. Note that it does not matter which solution we pick as our initial solution.

Using \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) as our initial solution and adding multiples of the period of tangent to this solution gives us the full set of solutions:

We can relate this solution set back to the intersection points on the graph above. When \(k=0\text{,}\) we get our initial solution of \(\frac{\pi}{4}\text{.}\) When \(k=1\text{,}\) we move to the right and get the next solution on the graph: \(\frac{5\pi}{4}\text{.}\) When \(k=-1\text{,}\) we get the solution to the left of our initial solution: \(-\frac{3\pi}{4}\text{,}\) and so on.

Not all trigonometric equations can be solved with the unit circle. To find the solutions to trigonometric equations with values not on the unit circle, we need to use the inverse trigonometric functions.

Use the inverse sine function to find one solution to \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{.}\)

Remember, the goal here is to obtain one value for \(\theta\text{.}\) Since \(-0.8\) is not a known unit circle value, we must apply the inverse sine function to solve for \(\theta\text{,}\) which gives us

To compute this value, we can use a calculator to find an approximate value for this angle. Remember that if your calculator is in degree mode, your calculator will give you an angle in degrees as the output. If your calculator is in radian mode, it will give you an angle in radians as the output. When solving trig equations for an angle, we will almost always want to find our answer in radians.

In radian mode, we get that \(\theta=\sin^{-1}(-0.8)\approx -0.927 \text{ radians}\text{.}\)

We can check our solution by evaluating \(\sin(-0.927)\) on our calculator. If our calculator returns a value close to \(-0.8\text{,}\) then the angle we have found is a solution to \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{.}\) Using our calculator (in radian mode), we get

Since this value is close to \(-0.8\text{,}\) we can be confident that this angle satisfies the equation \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{.}\)

Notice that the inverse trig functions do exactly what you would expect of any function - for each input, they give exactly one output. While this is necessary for these to be a function, it means that to find all the solutions to an equation like \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{,}\) we need to do more than just evaluate the inverse function.

Find all solutions to \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{.}\)

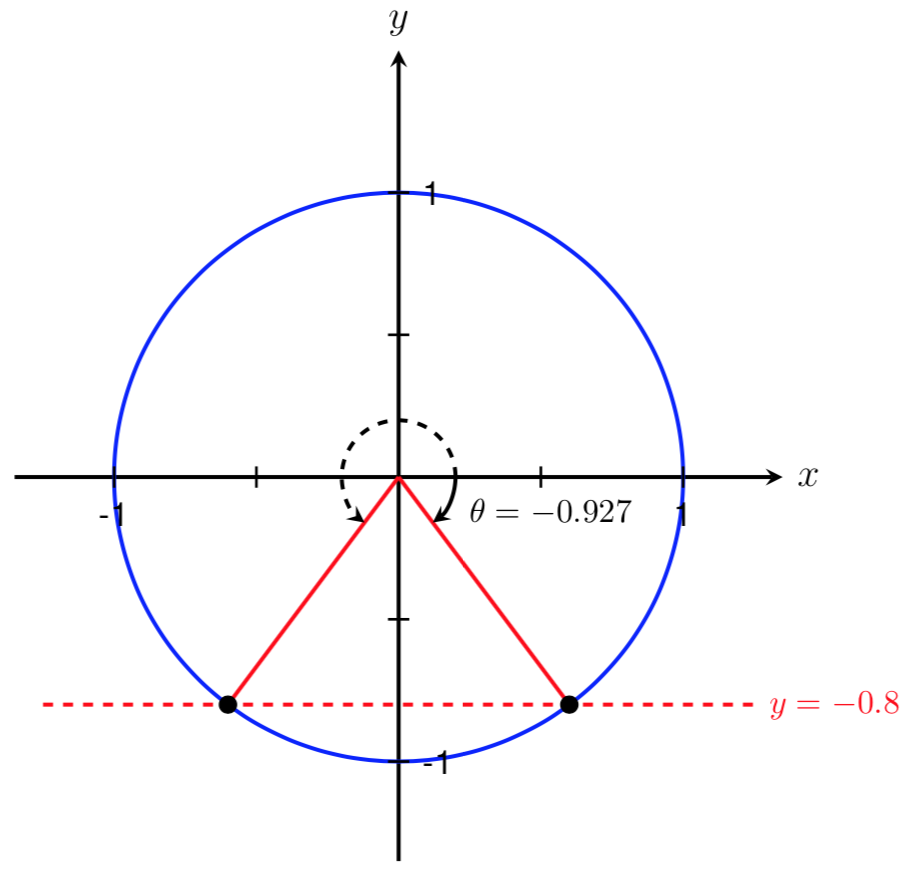

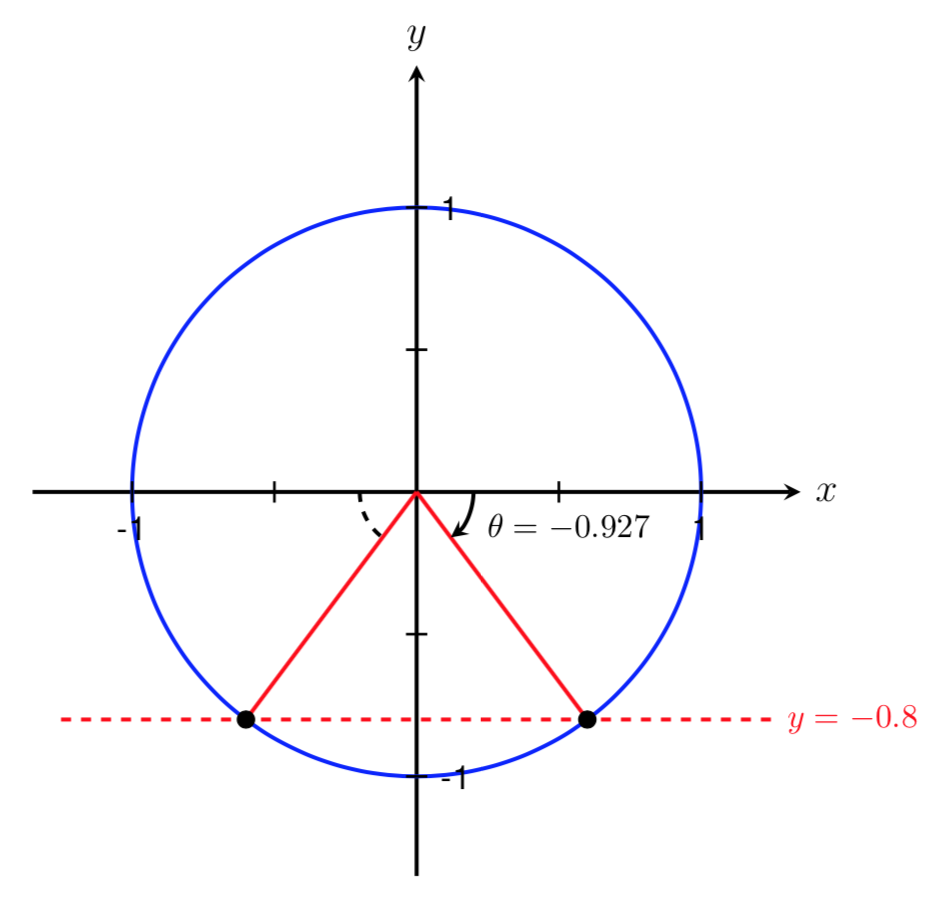

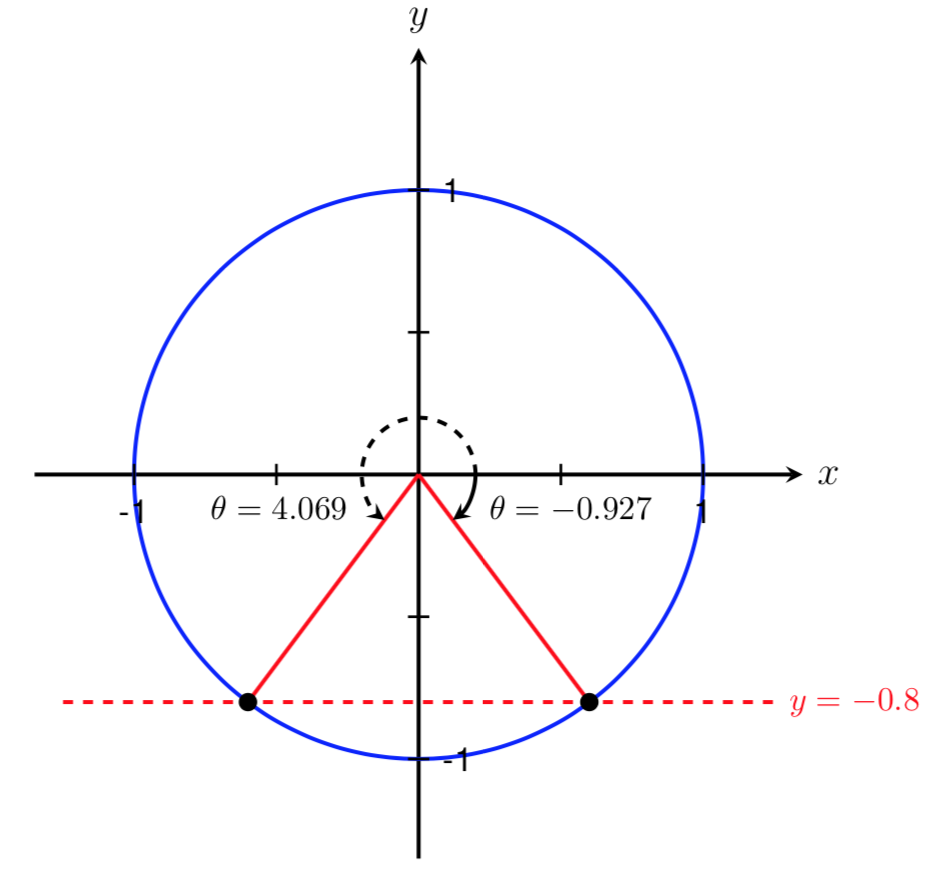

In the previous example, we found one solution to the equation \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{.}\) This angle corresponds to an angle on the unit circle with a \(y\)-value of \(-0.8\text{.}\) The angle that we found by using our calculator was \(\theta=-0.927\text{,}\) which lies in Quadrant IV since \(-0.927\) is less than \(0\) and bigger than \(-\frac{\pi}{2} \approx -1.571\text{.}\) However, we can also find a different angle that lies in Quadrant III with a sine value of \(-0.8\text{,}\) as shown below.

Before finding all solutions to \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{,}\) we must first find this other initial solution. We can use the symmetry of the unit circle to solve for this angle. By symmetry, the magnitudes of the two angles shown below are equal.

Therefore, to find this angle in Quadrant III, we can take the absolute value of the first angle we found and add this angle to \(\pi\text{.}\) This gives us an angle of

Again, we can check this solution to make sure that it satisfies the original equation by evaluating \(\sin(4.069)\) on our calculator and confirming that the value returned is close to \(-0.8\text{.}\) Doing this we get that \(\sin(4.069) = -0.8001\text{,}\) so we have found another angle satisfying \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\text{.}\)

We have now found our two initial solutions. However, if we look at the graph of \(f(\theta)=\sin(\theta)\) to see where it intersects with the horizontal line \(y=-0.8\text{,}\) we can see that there are an infinite number of solutions to the equation \(\sin(\theta) = -0.8\text{.}\)

These solutions, represented as intersection points on the graph, correspond to angles that are coterminal with the two initial solutions that we found above. To find all solutions, we can add multiples of the period, \(2\pi\text{,}\) to our initial solutions that we found above. Therefore, the set of all possible solutions to \(\sin(\theta)=-0.8\) is

It is helpful to remember four things when finding solutions to trigonometric equations:

The sine function corresponds to the \(y\)-value of a point on the unit circle.

The cosine function corresponds to the \(x\)-value of a point on the unit circle.

The tangent function is related to sine and cosine by

The sine and cosine functions have a period of \(2\pi\text{,}\) and the tangent function has a period of \(\pi\text{.}\)

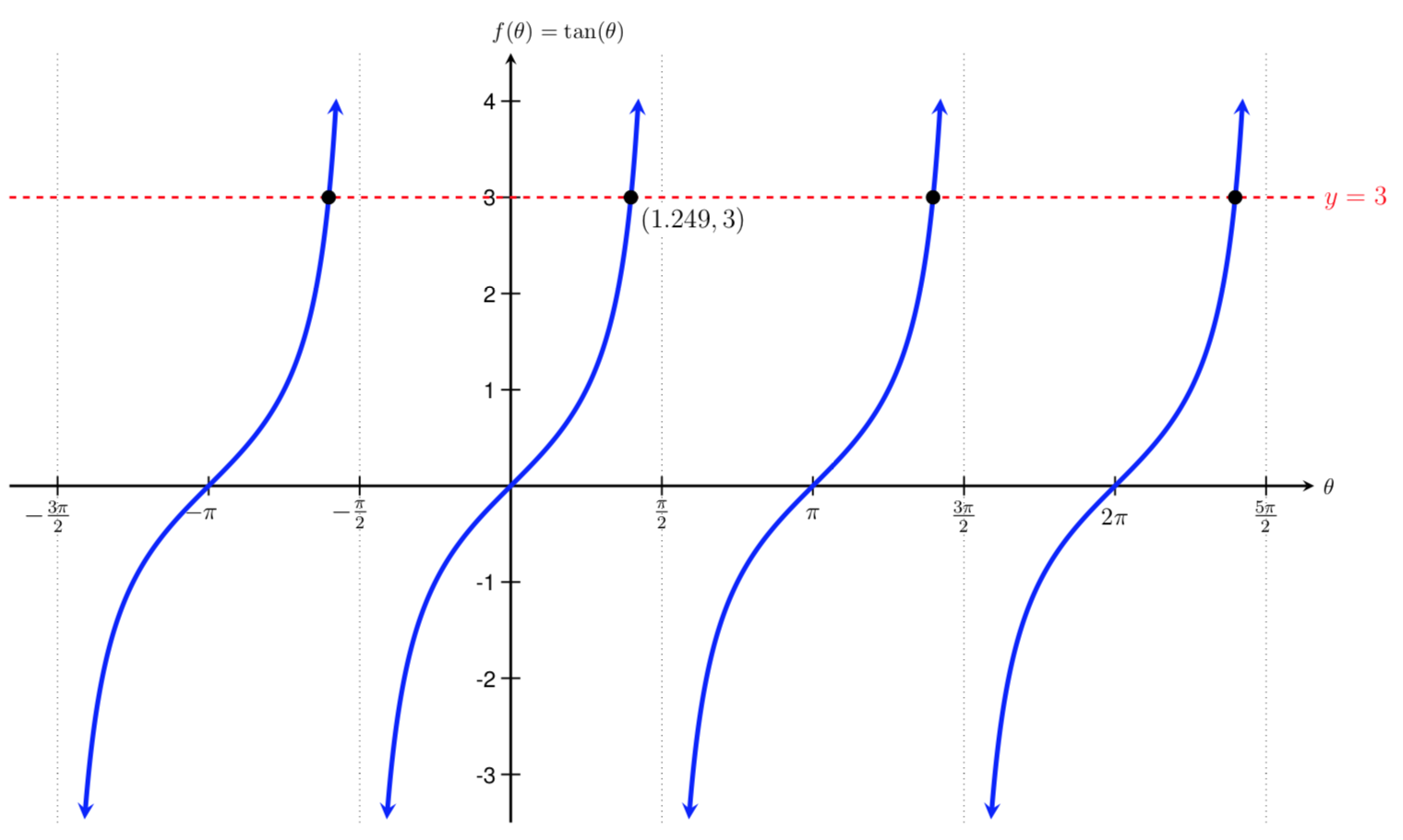

Find all solutions to \(\tan(\theta)=3\text{.}\)

Since there are no common angles on the unit circle for which \(\tan(\theta)=3\text{,}\) we must apply the inverse tangent function and solve for \(\theta\) approximately. We get that

Using our calculator to approximate this angle, we get

To check this solution, we can evaluate \(\tan(1.249)\) to see if we get a value close to 3. Using our calculator we get

Since this value is close to 3, we can be confident that the angle we have found satisfies the equation \(\tan(\theta)=3\text{.}\)

Now that we have found one solution, we can use \(\theta=1.249\) as our initial solution and solve for all other possible solutions. If we look at the graph of \(f(\theta)=\tan(\theta)\) to see where it intersects with the horizontal line \(y=3\text{,}\) we can see that there are an infinite number of solutions.

To find all possible solutions, we add multiples of the period, \(\pi\) to our initial solution, which gives us the solutions set

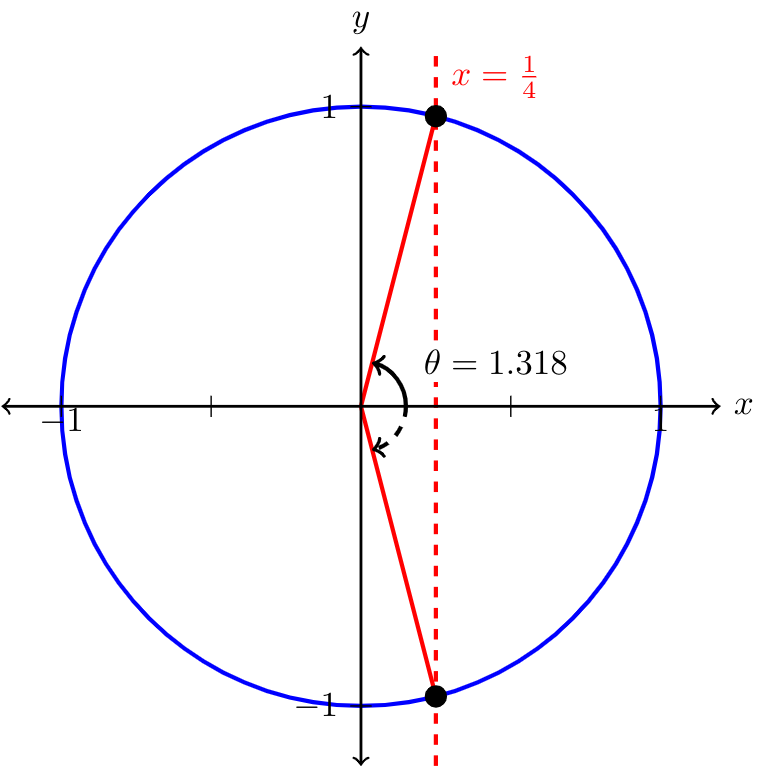

Find all solutions to \(\displaystyle \cos(\theta)=\frac{1}{4}\text{.}\)

Since there are no common angles on the unit circle for which \(\cos(\theta)=\frac{1}{4}\text{,}\) we must apply the inverse cosine function and solve for \(\theta\) approximately. Using our calculator, we get that

We can check this solution by evaluating \(\cos(1.318)\text{;}\) since \(\cos(1.318)\approx 0.2501\approx\frac{1}{4}\text{,}\) we can be confident that the angle we found satisfies \(\cos(\theta)=\frac{1}{4}\text{.}\)

Since \(\cos(1.318)\approx\frac{1}{4}\text{,}\) the angle \(\theta=1.318\) corresponds to an angle on the unit circle with a \(x\)-value of \(\frac{1}{4}\text{.}\) Since \(1.318\) is less than \(\frac{\pi}{2}\approx 1.57\) but greater than \(0\text{,}\) \(\theta\) lies in Quadrant I. We can find a different angle that lies in Quadrant IV with a \(x\)-value of \(\frac{1}{4}\text{,}\) as shown below.

We can use the symmetry of the unit circle to find this second angle. By symmetry, the second angle able is \(-\theta=-1.318\text{.}\) Again, we can check this solution to make sure it satisfies the original equation by evaluating \(\cos(-1.318)\) on our calculator. We get \(\cos(-1.318)\approx0.2501\approx\frac{1}{4}\text{,}\) so we have found another angle satisfying \(\cos(\theta)=\frac{1}{4}\text{.}\)

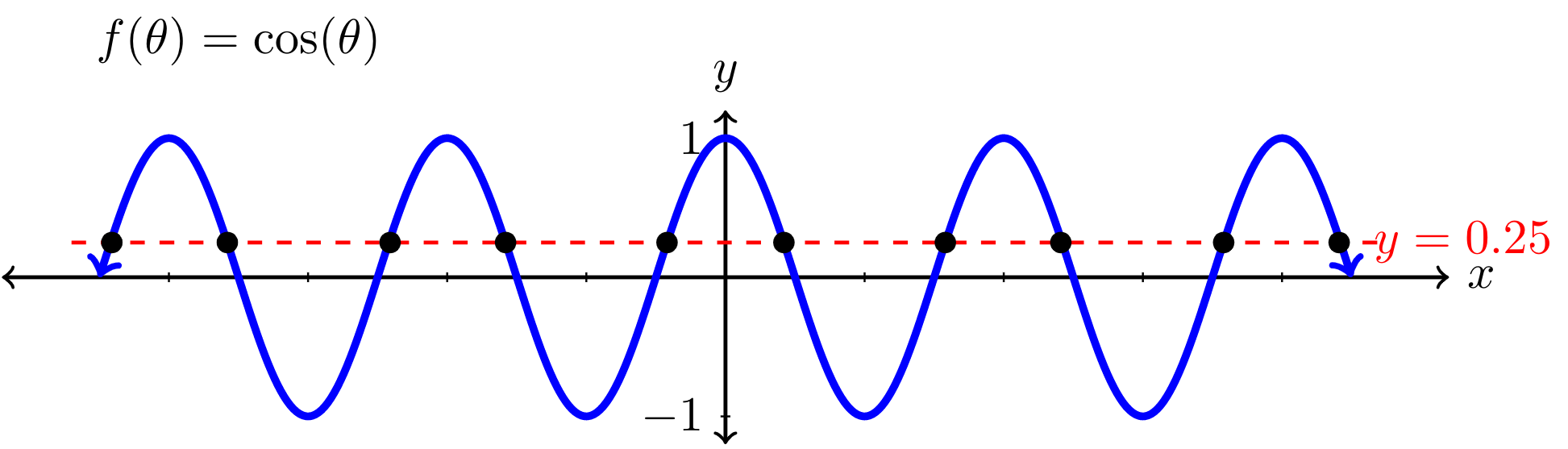

We have now found our two initial solutions. If we look at the graph of \(f(\theta)=\cos(\theta)\) to see where it intersects with the horizontal line \(y=\frac{1}{4}\text{,}\) we can see that there are an infinite number of solutions to the equation \(\cos(\theta)=\frac{1}{4}\text{.}\)

These solutions, represented as intersection points on the graph, correspond to angles that are coterminal with the two initial solutions that we found above. To find all solutions, we can add multiples of the period, \(2\pi\text{,}\) to our initial solutions that we found above. Therefore, the set of all possible solutions to \(\cos(\theta)=\frac{1}{4}\) is