Supplemental Videos

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

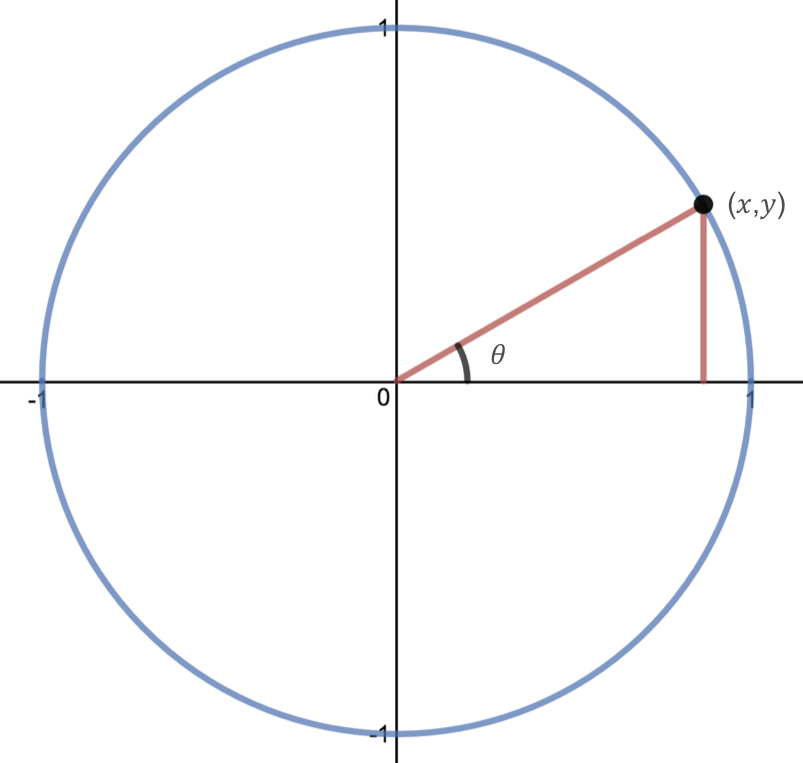

In the previous section, we defined the cosine and sine functions in terms of \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates on the unit circle. We also defined the cosine and sine of an angle as ratios of the sides of a right triangle. Since a triangle has 3 sides, there are 6 possible combinations of ratios of side lengths. While cosine and sine are the two prominent ratios that can be formed, there are four others, and together they define the 6 trigonometric functions.

Given an angle \(\theta \ \) (in either degrees or radians) and the \((x,y)\) coordinates of the corresponding point on the unit circle, we define tangent as

Just like sine and cosine, tangent is a function that takes angles as inputs.

Note that since \(\sin(\theta)=y\) and \(\cos(\theta)=x\text{,}\) we can also define tangent as

We can find the tangent values of common angles on the unit circle by using the sine and cosine values of the angles (or the corresponding \(y\) and \(x\) coordinates).

Find \(\tan(45^\circ)\text{.}\)

Since we know the sine and cosine values for \(45^\circ\text{,}\) it makes sense to relate the tangent value back to the sine and cosine values.

From the definition of tangent, we have that \(\, \displaystyle \tan(\theta)=\frac{\sin(\theta)}{\cos(\theta)} \, \) so

Find \(\tan\left(\frac{\pi}{3}\right)\text{.}\)

From the definition of tangent, we get that

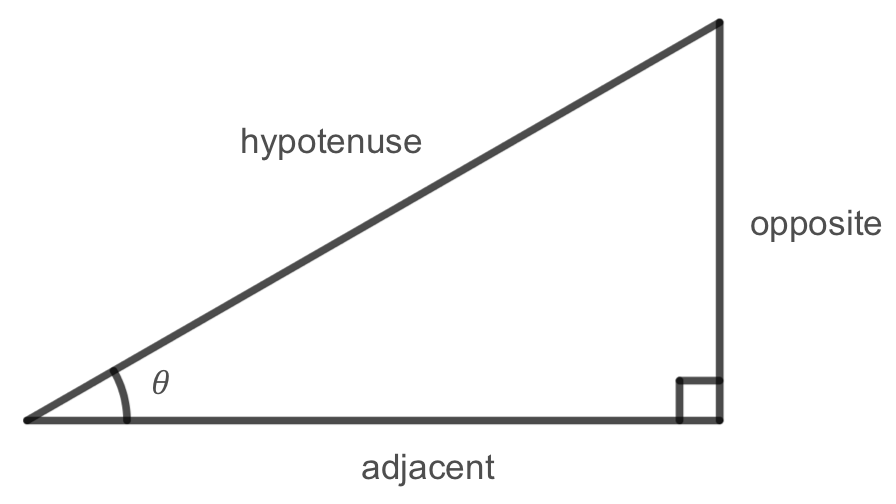

Like we did with sine and cosine, we can also state an equivalent, but more general definition of tangent using a right triangle.

Given a right triangle with an angle of \(\theta\text{,}\) we define tangent as

Tangent makes up the "Toa" part of the mnemonic Soh-Cah-Toa, which stands for "Tangent is opposite over adjacent."

Note that this definition of tangent is equivalent to the definition above since

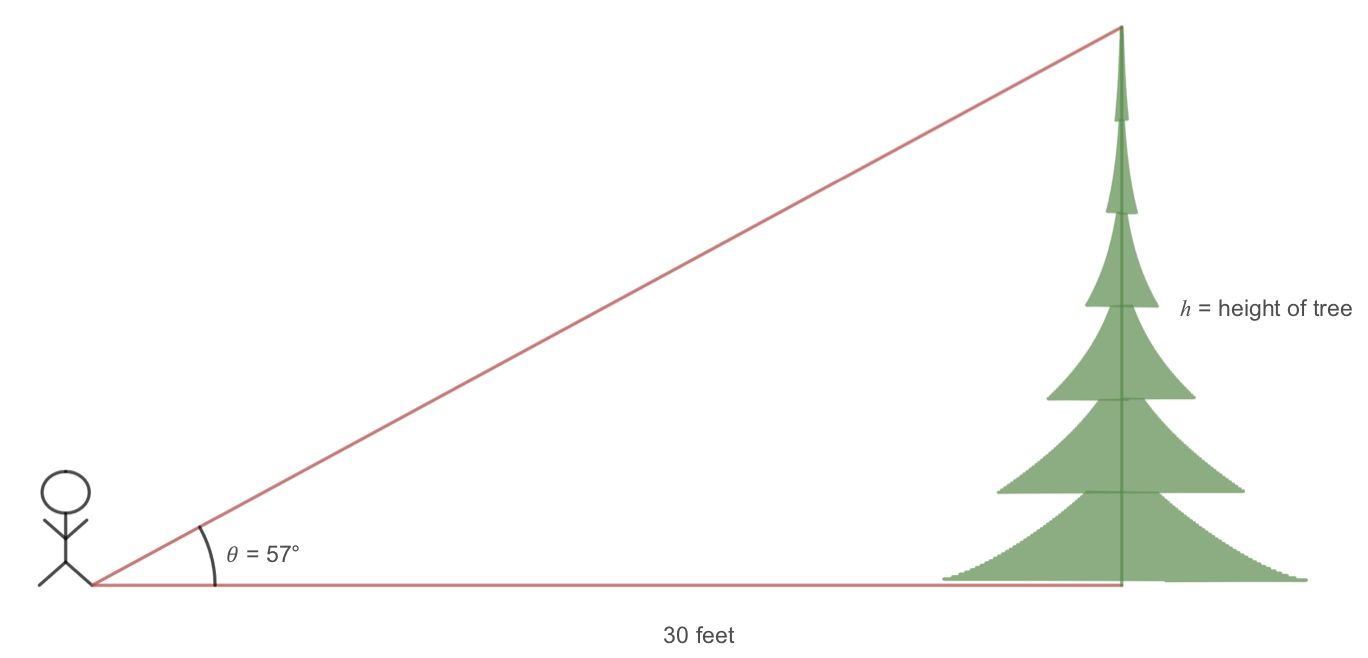

To find the height of a tree, a person walks to a point 30 feet from the base of the tree, and measures the angle from the ground to the top of the tree to be 57 degrees. Find the height of the tree.

Let's start by drawing a picture of the situation and labeling the known information.

We can introduce a variable, \(h\text{,}\) to represent the height of the tree. The two sides of the triangle that are most important to us are the side opposite of the \(57^\circ\) angle, which is the height of the tree that we are looking for, and the adjacent side, which is given as a distance of 30 feet.

The trigonometric function that relates the side opposite of the angle and the side adjacent to the angle is the tangent function. Using this function, we can set up an equation and solve to find \(h\text{.}\)

The tree is approximately 46.2 feet tall.

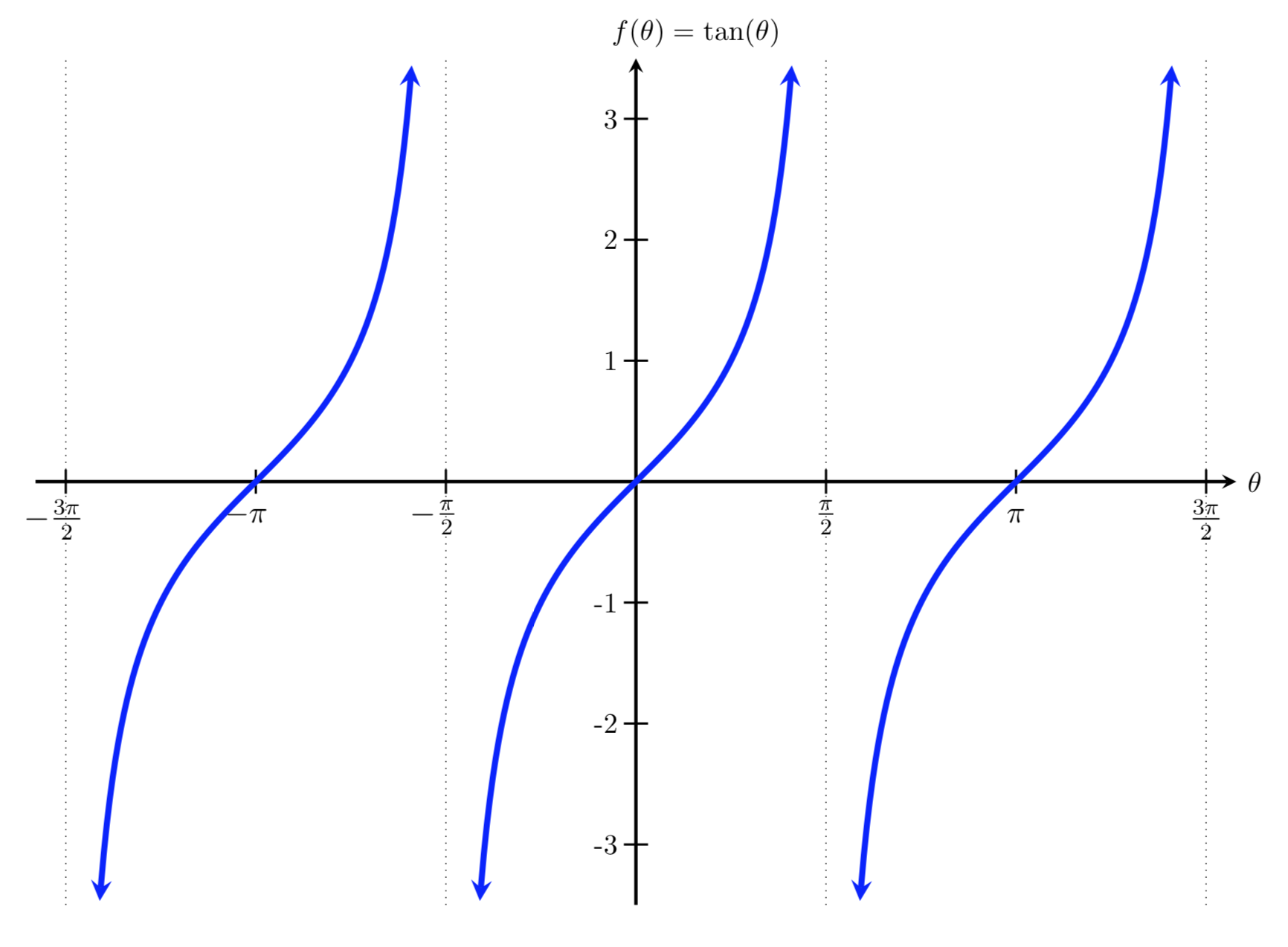

Because the tangent function is defined by a quotient, it has a restricted domain. The tangent function is undefined if the denominator is zero, which occurs exactly when \(\cos(\theta)=0\text{.}\) On the interval \([0,2\pi]\text{,}\) \(\cos(\theta)=0\) when \(\theta=\frac{\pi}{2}\) or \(\theta=\frac{3\pi}{2}\text{.}\) This means that \(\frac{pi}{2}\) and \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) are not in the domain of the tangent function. If we consider the tangent function on a larger interval than \([0,2\pi]\text{,}\) even more values might be excluded from the domain.

Just like we did with the sine and cosine functions in the previous Section, we can sketch a graph of the tangent function by creating a table of input and output values and plotting these points on a plane. Below is a table of values for \(f(\theta) = \tan(\theta)\) and its corresponding graph.

\begin{equation*}

\theta

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \ \ 0 \ \ \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\pi}{6}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \ \frac{\pi}{4} \ \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \frac{\pi}{3} \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\pi}{2}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{2\pi}{3}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \frac{3\pi}{4} \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{5\pi}{6}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \ \ \pi \ \ \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{7\pi}{6}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \frac{5\pi}{4} \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \frac{4\pi}{3} \

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{3\pi}{2}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\tan(\theta)

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

0

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

1

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\ \sqrt{3} \

\end{equation*}

|

undef. |

\begin{equation*}

-\sqrt{3}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

-1

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

0

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{3}

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

1

\end{equation*}

|

\begin{equation*}

\sqrt{3}

\end{equation*}

|

undef. |

Notice that the output values of tangent repeat on a regular interval, so \(f(\theta) = \tan(\theta)\) is a periodic function. For any angle, there is a second angle halfway around the unit circle with the same tangent value. Therefore, the period of tangent is \(\pi\text{.}\) We can see one continuous cycle from \(-\pi/2\) to \(\pi/2\text{,}\) before the graph jumps and repeats itself.

The graph of tangent has no maximum or minimum value. Therefore, as you may recall from Note5, tangent is an example of a periodic function with no midline or amplitude.

Explain how the tangent function is related to the slope of a line going through the origin and a point \((x,y)\) on the unit circle.

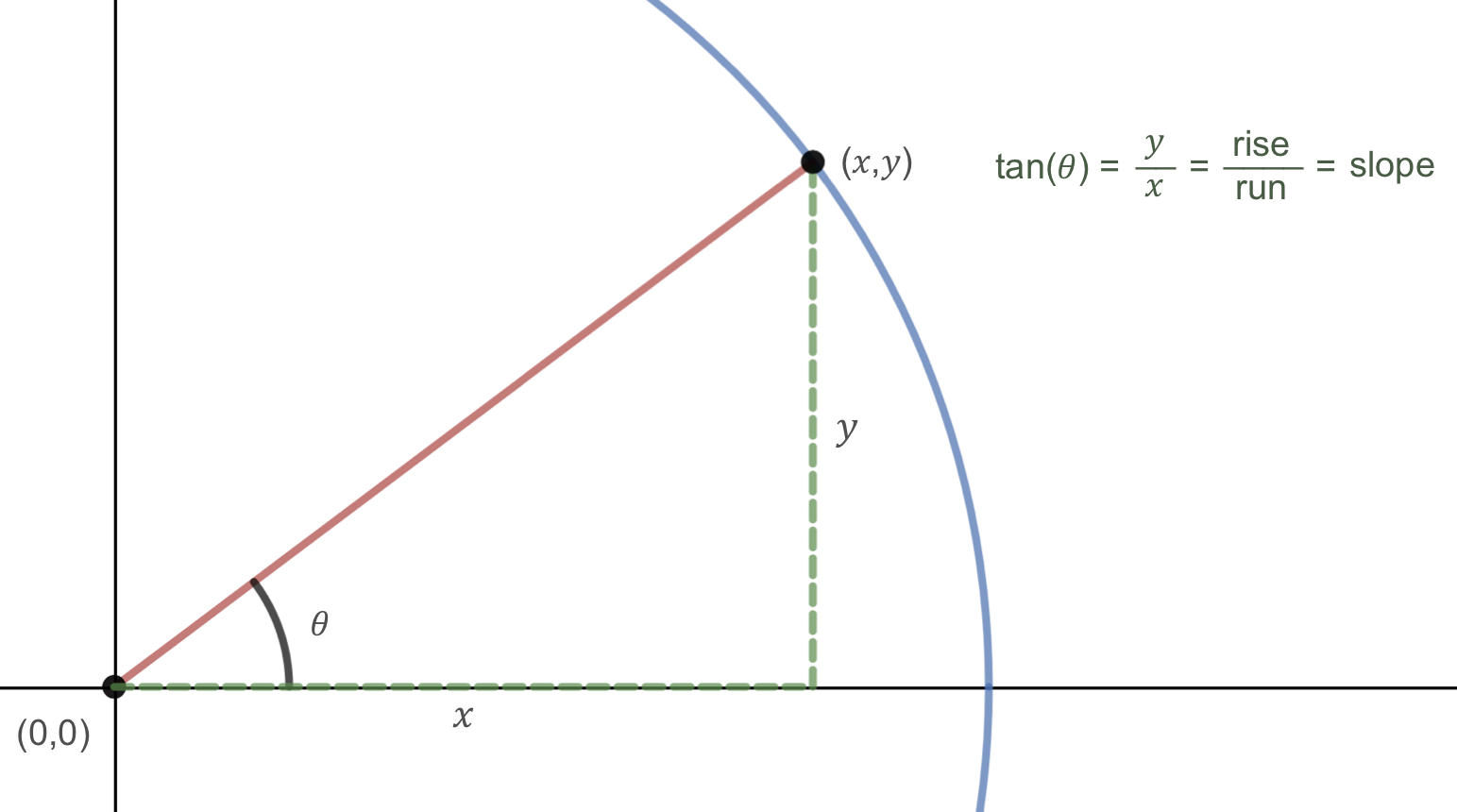

One way we can think about the graph of tangent is to relate the tangent function to the slope of a line going through the origin and a point \((x,y)\) on the unit circle. Above, we defined tangent as

where \(x\) and \(y\) are the coordinates of a point on the unit circle corresponding to a given angle \(\theta\text{.}\) Now, notice that \(y/x\) corresponds to the slope of a line through the origin. Therefore, the tangent of an angle, \(\theta\text{,}\) is equal to the slope of a line going through the origin making an angle of \(\theta\) with the positive \(x\)-axis.

We can also relate this concept to the graph of tangent. At an angle of 0, the line would be horizontal with a slope of zero. This corresponds to the value of \(\tan(0)=0\text{,}\) or where the graph of tangent passes through the origin. As the angle increases towards \(\pi/2\text{,}\) the slope of the line increases more and more. At an angle of \(\pi/2\text{,}\) the line would be vertical and the slope would be undefined. Immediately past \(\pi/2\text{,}\) the line would have a steep negative slope, corresponding to a large negative value of tangent. The undefined slope at \(\pi/2\) corresponds to a vertical asymptote on the graph, where the tangent value jumps from a large positive value to a large negative value.