Supplemental Videos

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

So far, we have defined the sine, cosine, and tangent functions. There are three more trigonometric functions, which we define in this section. We will also explore relationships between the six trigonometric functions.

There are times when it can be useful to consider functions like \(1/\sin(\theta)\) or \(1/\cos(\theta)\text{.}\) This happens often enough that mathematicians have created special names for these types of functions. Generally, these functions are called reciprocal trigonometric functions, and they can be defined in terms of the sine, cosine, and tangent functions.

Given an angle \(\theta\text{,}\) we define:

Find \(\sec\left(\frac{5\pi}{6}\right)\text{,}\) \(\csc\left(\frac{5\pi}{6}\right)\text{,}\) and \(\cot\left(\frac{5\pi}{6}\right)\text{.}\)

Since \(\frac{5\pi}{6}\) is a common angle on the unit circle, we have that

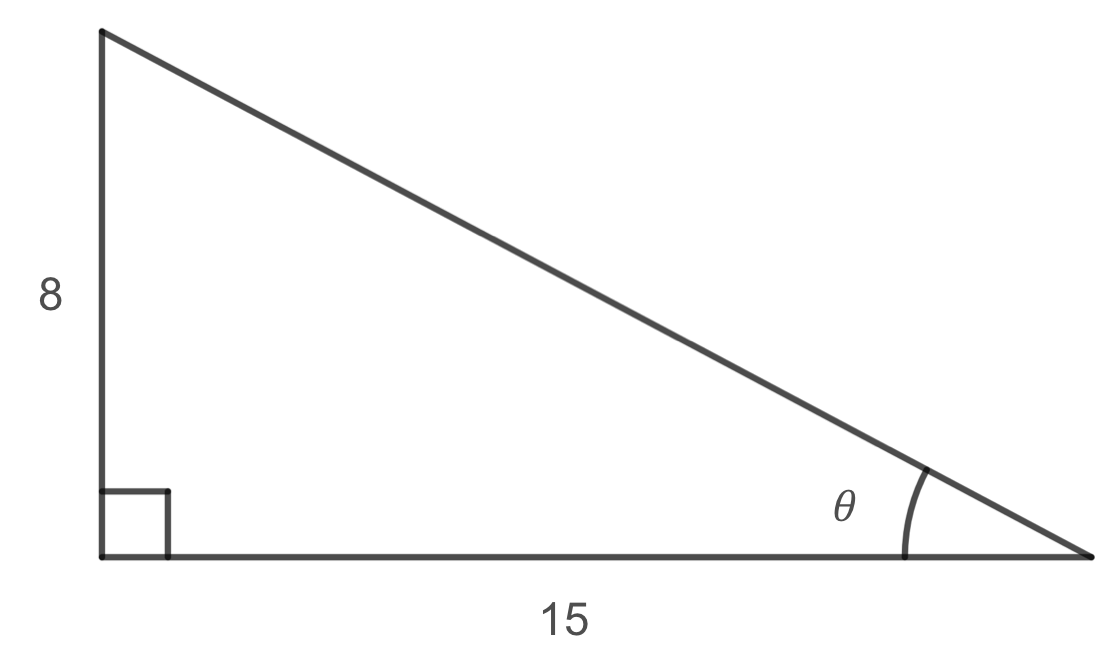

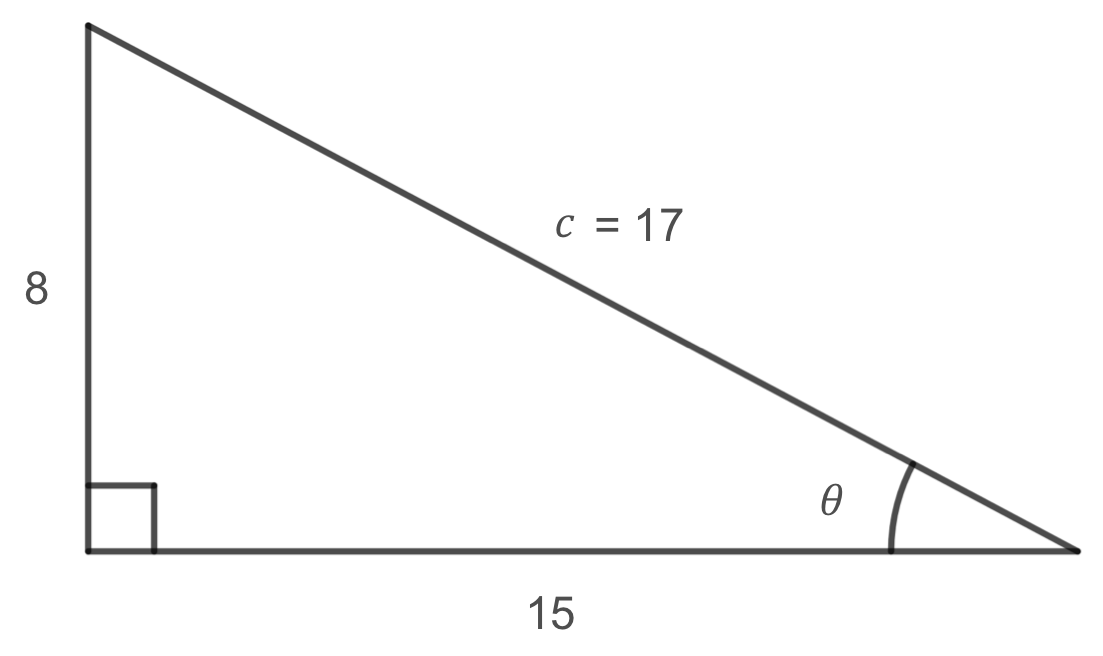

Using the triangle shown, evaluate \(\sec(\theta)\text{,}\) \(\csc(\theta)\text{,}\) and \(\cot(\theta)\text{.}\)

To find values for reciprocal trigonometric functions, we must first find values for \(\cos(\theta)\text{,}\) \(\sin(\theta)\text{,}\) and \(\tan(\theta)\text{.}\) We must also find the length of the hypotenuse. Letting the variable \(c\) represent the length of the hypotenuse and using the Pythagorean Theorem, we get that

Now solving for \(\cos(\theta)\text{,}\) \(\sin(\theta)\text{,}\) and \(\tan(\theta)\text{,}\) we get that

Finally, solving for the reciprocal trigonometric functions, we get

Trigonometric functions are related to each other in special ways. In the last part of this section, we explored how sine, cosine, and tangent are related to the reciprocal trig functions cosecant, secant, and cotangent. We now return to Example30 from the previous Section to illustrate a special relationship between sine and cosine.

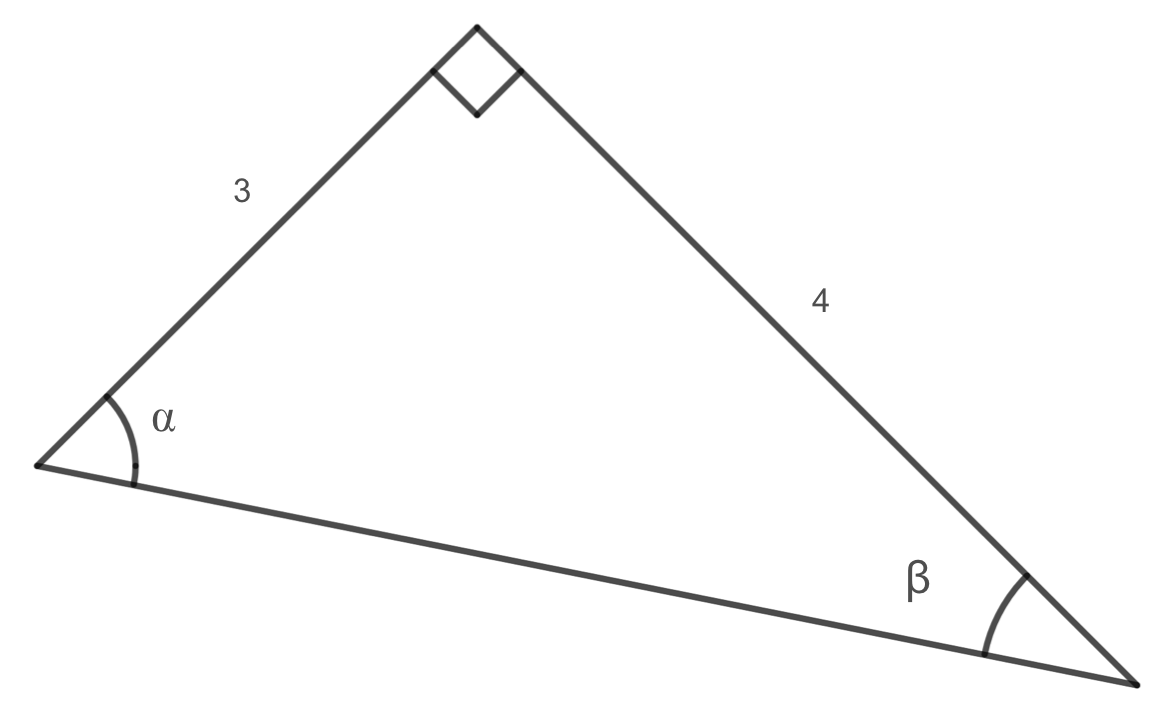

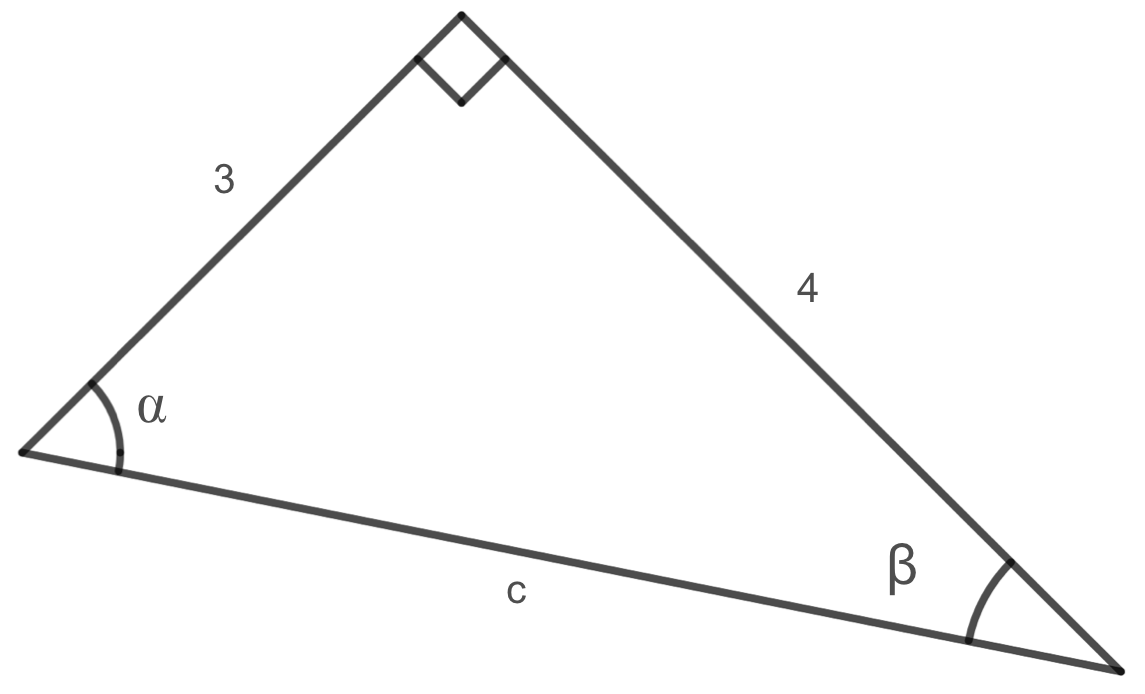

Using the triangle shown below, find \(\cos(\alpha)\text{,}\) \(\sin(\alpha)\text{,}\) \(\cos(\beta)\text{,}\) and \(\sin(\beta)\text{.}\)

Before solving for the cosine and sine values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\text{,}\) we must first find the length of the hypotenuse. Using the Pythagorean theorem, we get that

Now solving for the cosine and sine values of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\text{,}\) we get that

You may have noticed in the previous example that \(\cos(\alpha) = \sin(\beta)\) and \(\cos(\beta) = \sin(\alpha)\text{.}\) If we think about Soh-Cah-Toa and the right triangle relationships, the side opposite of \(\alpha\) is the side that is adjacent to \(\beta\) so it would make sense that \(\cos(\alpha) = \sin(\beta)\text{.}\) Since the three angles in a triangle need to add to \(\pi\text{,}\) or 180 degrees, then the angles \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) must add to \(\pi/2\text{,}\) or 90 degrees, so \(\alpha + \beta = \pi/2\) and we have that

Since \(\cos(\alpha) = \sin(\beta)\text{,}\) we get that

Two functions are called cofunctions if they are equal on complementary angles (angles that add up to 90 degrees or \(\pi/2\) radians).

Sine and cosine are examples of cofunctions (hence the "co" in cosine). The cofunction identities for sine and cosine are

Secant and cosecant are another example of cofunctions as are tangent and cotangent, which gives us two more sets of identities.

Recall that a function is called even if \(f(x)=f(-x)\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\text{.}\) A function is called odd if \(f(x)=-f(-x)\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\text{.}\) If you would like to review these concepts in further detail, please refer to Reflection and Even and Odd Functions.

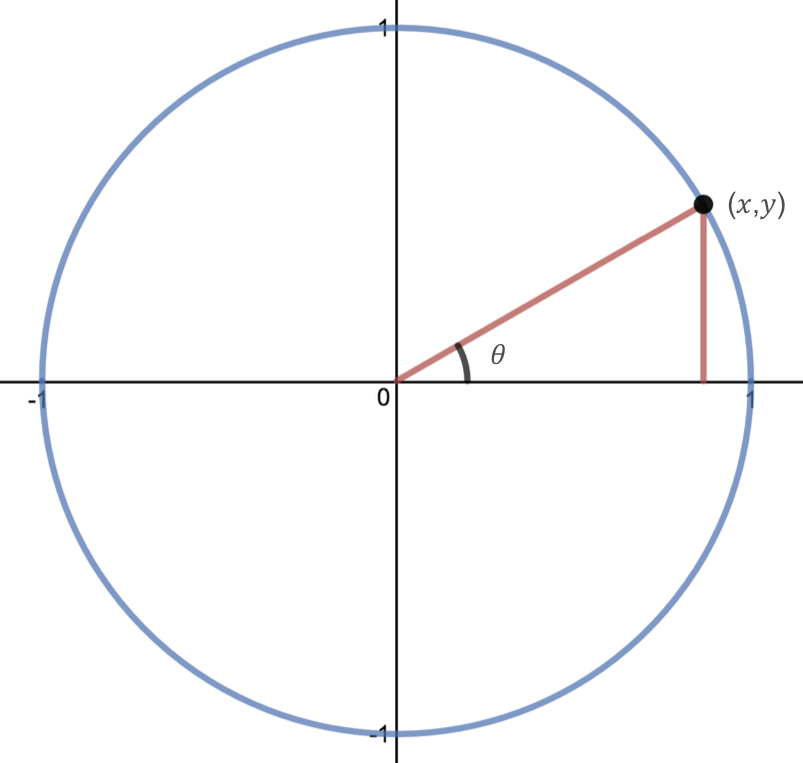

Now, suppose that \(\theta \) is an angle in the first quadrant. Then recall that the \((x,y)\) coordinates of the corresponding point on the unit circle satisfy the equations

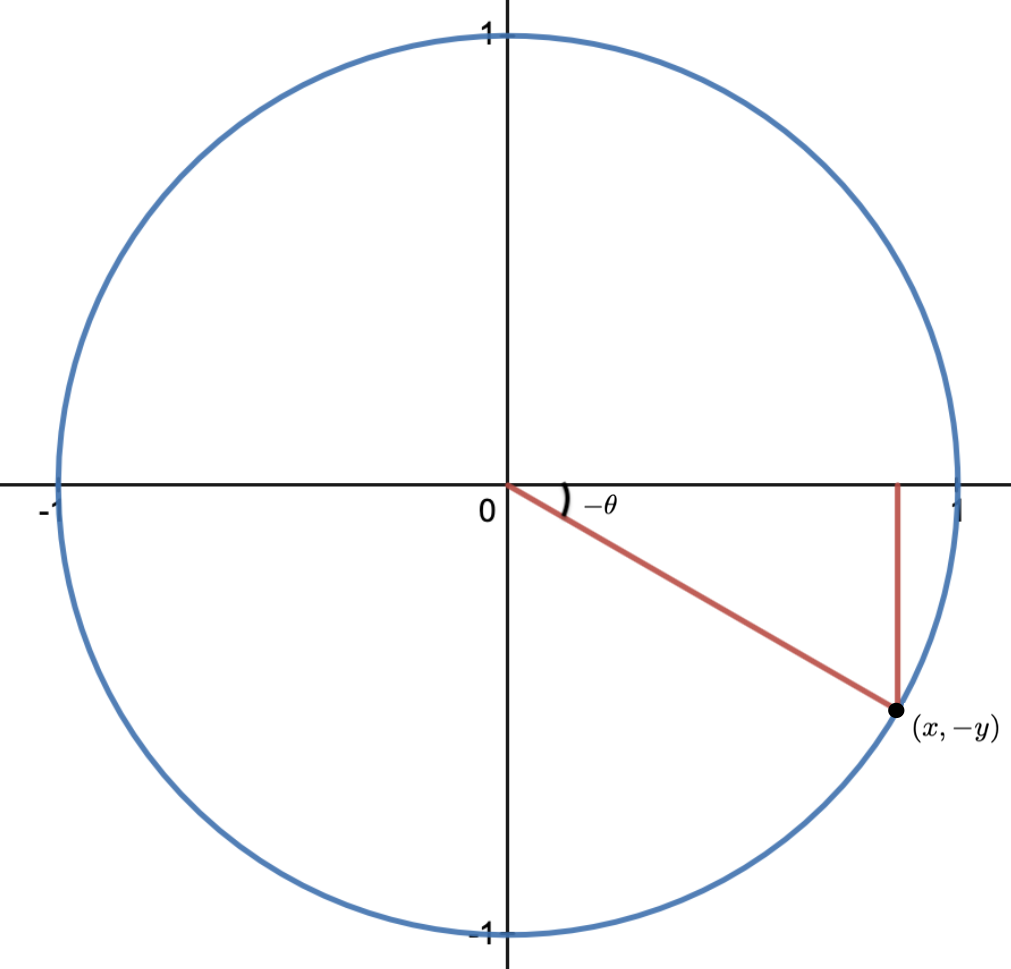

Then if we consider the angle \(-\theta \text{,}\) which is in the fourth quadrant, we can draw the following picture:

And use it to conclude that

As an exercise, you can check that these equations are also true for angles in the second, third, and fourth quadrants. Therefore, we can conclude that sine is an odd function and that cosine is an even function.

We can use the definition of tangent, and the even and odd properties of cosine and sine, respectively, to show that tangent is an odd function:

Our findings are summarized below.

Cosine is an even function, i.e.

Sine is an odd function, i.e.

Tangent is an odd function, i.e.

Find \(\sin(-\theta+4\pi)\) given that \(\sin(\theta)=\frac{1}{3}\text{.}\)

Recall that sine is \(2\pi\) periodic. This means that the value of the sine function is same same whenever the input differs by \(2\pi\text{;}\) in other words, if two angles are coterminal, then they have the same output in the sine function. Therefore

Since sine is a odd function, \(\sin(-\theta)=-\sin(\theta)\text{,}\) so

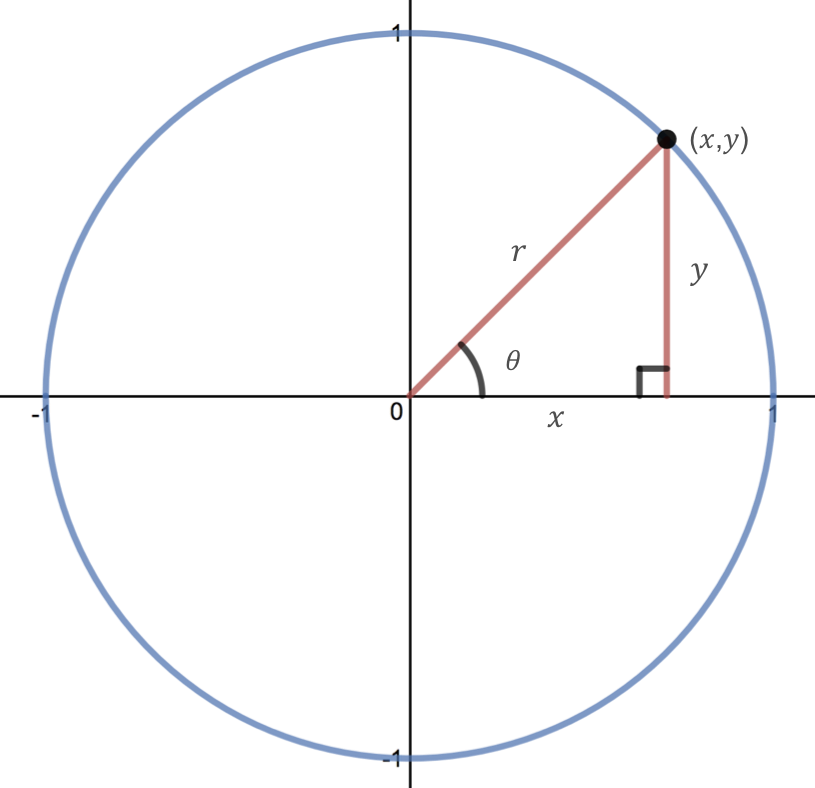

The relationship between right triangles and trigonometric functions of angles on the unit circle can also be used to derive a new identity. Consider the same right triangle we used above.

By using the Pythagorean Theorem and the definitions of cosine and sine, we can establish a new identity. We start by relating the sides of the right triangle shown above using the Pythagorean Theorem.

This result is known as the Pythagorean Identity.

As shown above, \(\cos^2(\theta)\) and \(\sin^2(\theta)\) are commonly used shorthand notations for \((\cos(\theta))^2\) and \((\sin(\theta))^2\text{.}\) Be aware that some calculators and computers may not understand the shorthand notation.

For any angle \(\theta\text{,}\)

The Pythagorean Identity can help us to find a cosine value of an angle if we know the sine value of that angle or vice versa. However, solving the equation will yield two possible values, so we will need to utilize additional knowledge of the angle to help us find the desired value.

If \(\displaystyle \sin(\theta)=\frac{3}{7}\) and \(\theta\) is in the second quadrant, find \(\cos(\theta)\text{.}\)

Substituting the known value for sine into the Pythagorean identity, we have

Since \(\theta\) is in the second quadrant, we know the \(x\) value of the corresponding point on the unit circle is negative. Therefore, the cosine value should also be negative. Using this additional information, we can conclude that