Supplemental Videos

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

The main topics of this section are also presented in the following videos:

Before we begin discussing the behavior of power functions, it is important that we remember our laws of exponents. Recall that a positive integer exponent tells us how many times its base occurs as a factor in an expression. For example,

Recall too the definition of a negative or zero exponent: Definition of Negative and Zero Exponents

As we begin combining both positive and negative exponents, we adhere to the following rules:

\(\displaystyle{a^m\cdot a^n = a^{m+n}}\)

\(\displaystyle{\frac{a^m}{a^n}=a^{m-n}}\)

\(\displaystyle{\left(a^m\right)^n=a^{mn}}\)

\(\displaystyle{\left(ab\right)^n=a^n b^n}\)

\(\displaystyle{\left(\frac{a}{b}\right)^n=\frac{a^n}{b^n}}\)

\begin{align*} \text{a}\amp. ~x^3\cdot x^{-5} = x^{3-5} = x^{-2} \amp\amp \text{Apply the first law: Add exponents.} \\ \text{b}\amp. ~\frac{8x^{-2}}{4x^{-6}}= \frac{8}{4}x^{-2-(-6)} = 2x^4 \amp\amp \text{Apply the second law: Subtract exponents.} \\ \text{c}\amp. ~\left(5x^{-3}\right)^{-2}= 5^{-2}(x^{-3})^{-2}=\frac{x^6}{25} \amp\amp \text{Apply laws IV and III.} \end{align*}

You can check that each of the calculations in Example308 is shorter when we use negative exponents instead of converting the expressions into algebraic fractions.

Simplify by applying the laws of exponents.

\(\left(2a^{-4}\right) \left(-4a^2\right)\)

\(\dfrac{(r^2)^{-3}}{3r^{-4}}\)

\((2a^{-4})(-4a^2)=-8a^{-4+2}=-8a^{-2}=\dfrac{-8}{a^2} \)

\(\dfrac{(r^2)^{-3}}{3r^{-4}}=\dfrac{r^{-6}}{3r^{-4}}=\dfrac{1}{3r^2} \)

The laws of exponents do not apply to sums or differences of powers. We can add or subtract like terms, that is, powers of the same variable with the same exponent. For example,

but we cannot add or subtract terms with different exponents. Thus, for example, \begin{align*} 4x^2 \amp- 3x^{-2} \amp\amp \text{cannot be simplified, and}\\ x^{-1} \amp + x^{-3}\amp\amp \text{cannot be simplified}. \end{align*}

A function of the form

where \(k\) is a nonzero constant and \(p\) is any constant, is called a power function. In particular, if \(p=0\text{,}\) then \(f(x)\) is the constant function \(f(x) = k\text{.}\)

Examples of power functions are

In addition, the basic functions

can be written as

Their graphs are shown in Figure311. Note that the domains of power functions with negative exponents do not include zero.

Which of the following are power functions?

\(f (x) = \dfrac{1}{3}x^4 + 2\)

\(g(x) = \dfrac{1}{3x^4}\)

\(h(x) = \dfrac{x + 6}{x^3}\)

This is not a power function, because of the addition of the constant term.

We can write \(g(x) = \frac{1}{3}x^{-4}\text{,}\) so \(g\) is a power function.

This is not a power function, but it can be treated as the sum of two power functions, because \(h(x) = x^{-2} + 6x^{-3}\text{.}\)

Write each function as a power function in the form \(y = kx ^p\text{.}\)

\(f (x) = {12}{x^2}\)

\(g(x) = \dfrac{1}{4x}\)

\(h(x) = \dfrac{2}{5x^6}\)

\(f (x) = 12x^{-2}\)

\(g(x)=\dfrac{1}{4}x^{-1} \)

\(h(x)=\dfrac{2}{5}x^{-6} \)

While power functions do not in general have to have integer exponents, these will be the types of power functions we are most interested in. In particular, we will look at the graphs and long run behavior of power functions with integer exponents. By long run behavior of a function we mean the value the function approaches as the input \(x \) goes to infinity or negative infinity.

Recall that the graph of \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\) and \(g(x)=\frac{1}{x^2}\) are given by:

Let's begin with the long run behavior of \(f(x) \text{.}\) Looking at the graph, we see that as \(x \) goes to infinity (i.e. as we move farther to the right on the \(x \)-axis) the output values of \(f(x)\) are getting close to 0. Similarly, as \(x \) goes to negative infinity (as we move farther to the left on the \(x\)-axis) the output values of \(f(x)\) are also getting closer to 0. We write this as

By identical reasoning as above, we also have that

In general, we have the following behaviors of power functions with integer exponents:

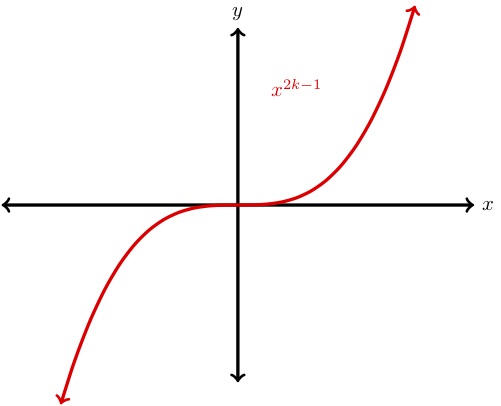

The graph of

is shown to the right. The long run behavior of such a function is given by \begin{align*} x^\text{(odd positive number)}\to -\infty\ \amp \text{as}\ x\to -\infty\ ,\ \ \text{and}\\ x^\text{(odd positive number)}\to \infty\ \amp \text{as}\ x\to \infty. \end{align*} Examples of such functions are \(x,x^3,x^5,\) etc.

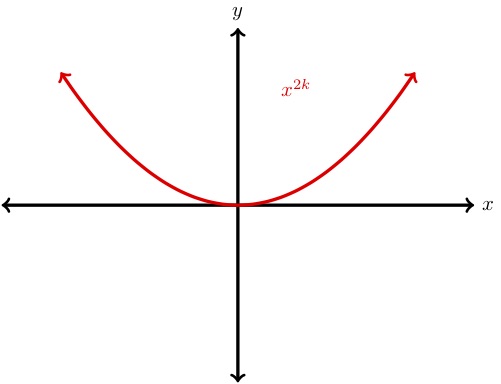

The graph of

is shown to the right. The long run behavior of such a function is given by \begin{align*} x^\text{even positive number}\to \infty\ \amp \text{as}\ x\to \pm\infty. \end{align*} Examples of such functions are \(x^2,x^4,x^6,\) etc.

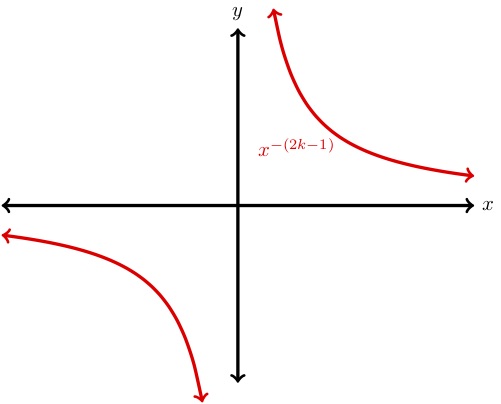

The graph of

is shown to the right. The long run behavior of such a function is given by \begin{align*} x^\text{odd negative number}\to 0\ \amp \text{as}\ x\to \pm\infty. \end{align*} Examples of such functions are \(x^{-1},x^{-3},x^{-5},\) etc.

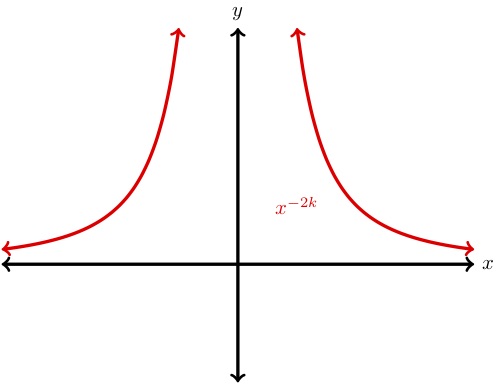

The graph of

is shown to the right. The long run behavior of such a function is given by \begin{align*} x^\text{even negative number}\to 0\ \amp \text{as}\ x\to \pm\infty \end{align*} Examples of such functions are \(x^{-2},x^{-4},x^{-6},\) etc.