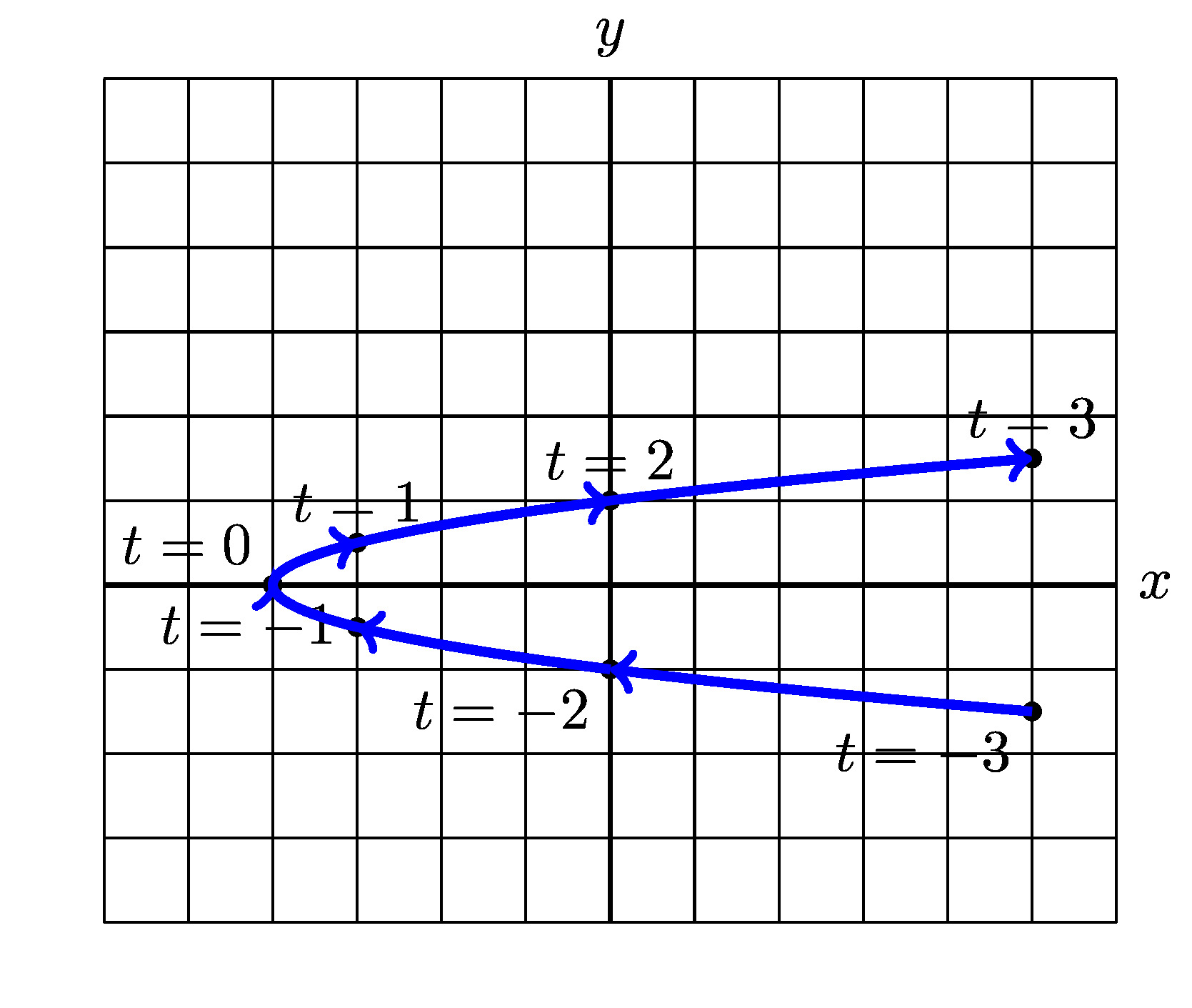

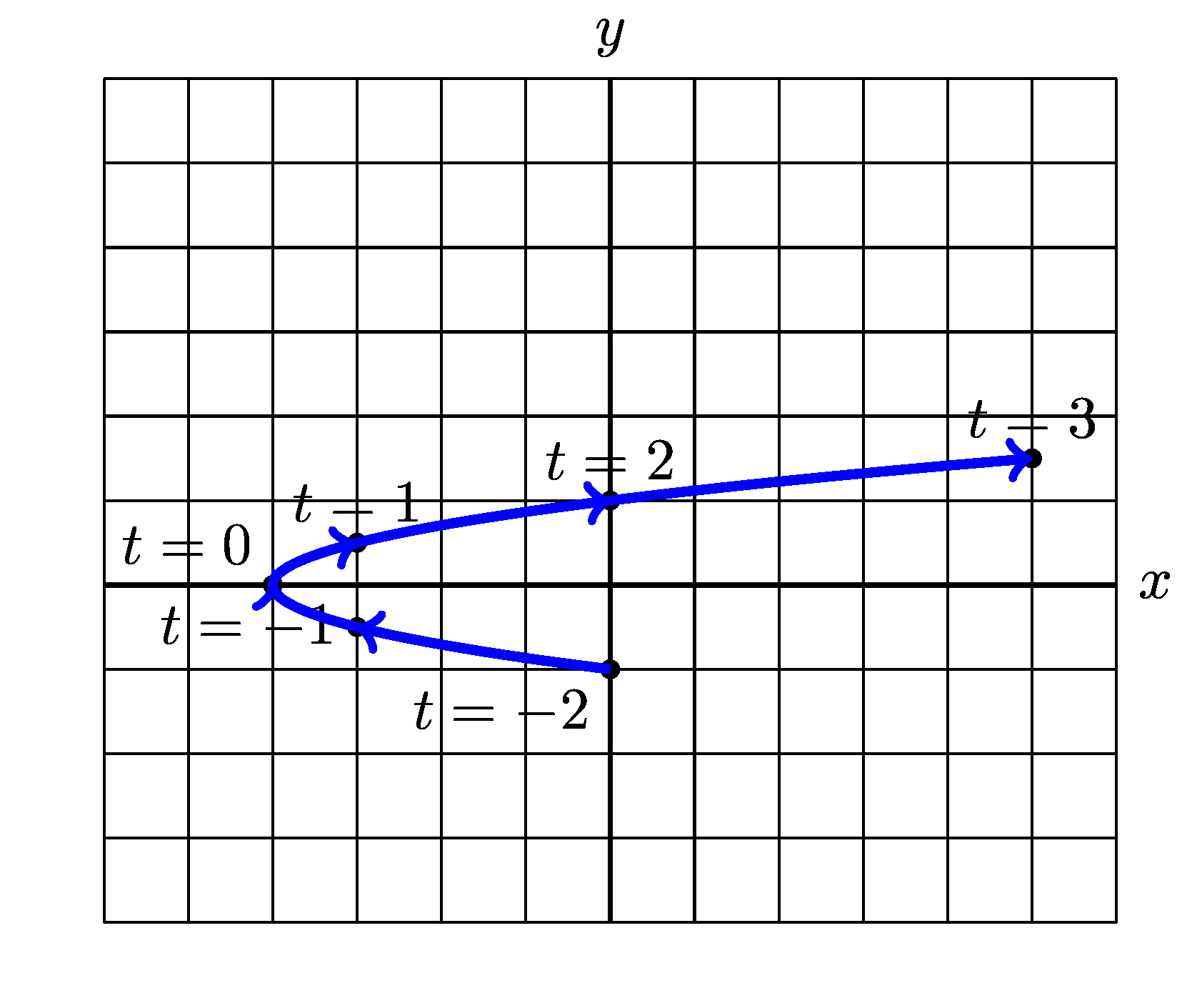

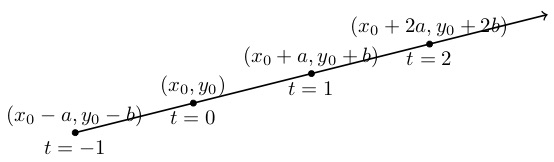

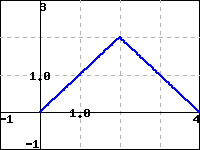

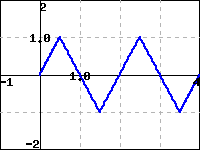

A reasonable first step is to cerate a table of values for \(t=-2,-1,0,1,2,3\text{.}\) Why these values of \(t\text{?}\) Choosing "good" values of \(t\) is not always a straight forward task and in general you must choose values that give you a "reasonable" picture of the curve. You also might wonder how many values of \(t\) are appropriate. Again, the answer is enough values that you can be reasonably confident you have captured the shape of the curve. So what does this mean? Often it helps to choose a few positive and negative values close to zero, calculate these values, plot the points, and then determine if you need more values to give your curve a clear shape.