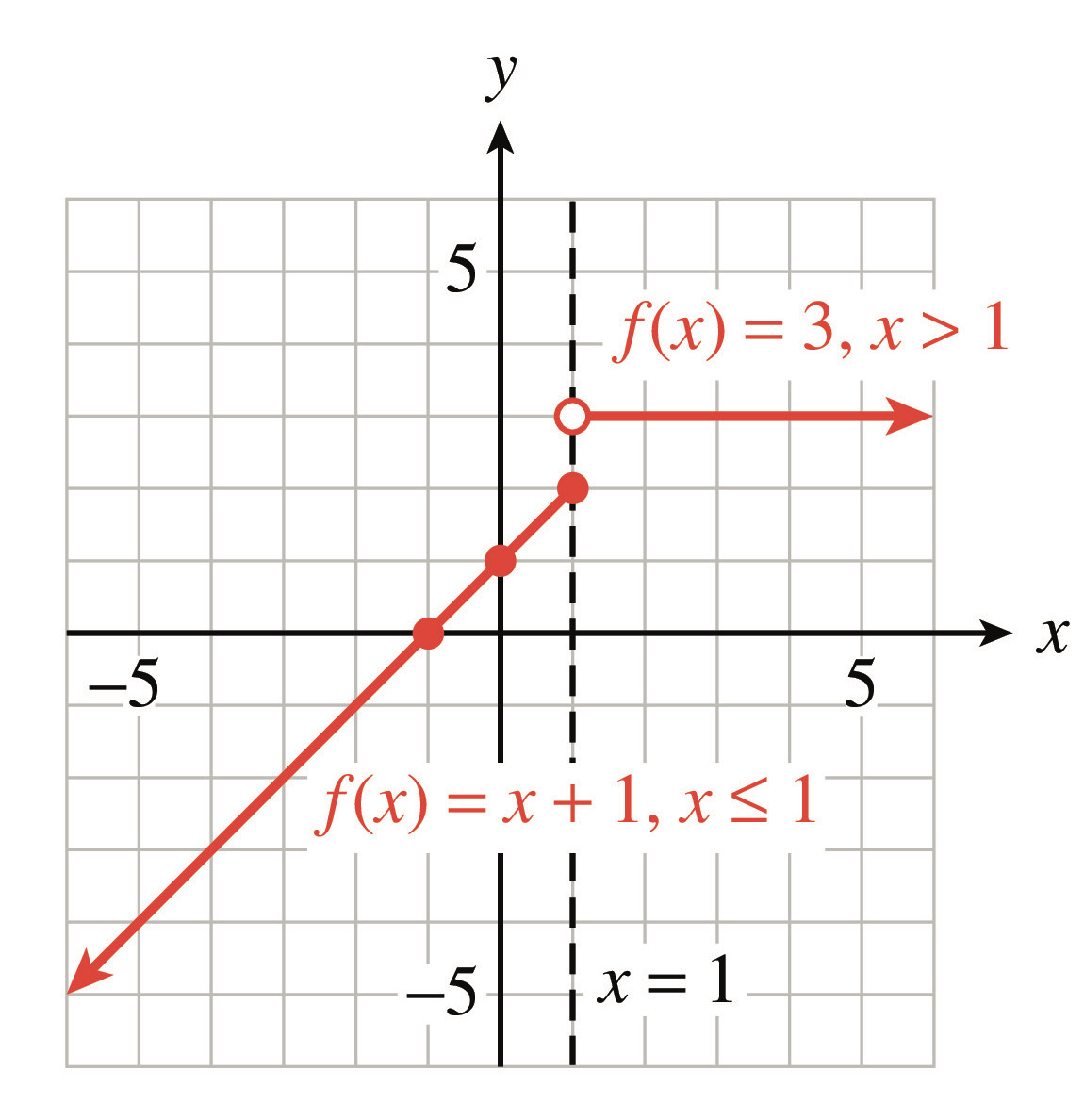

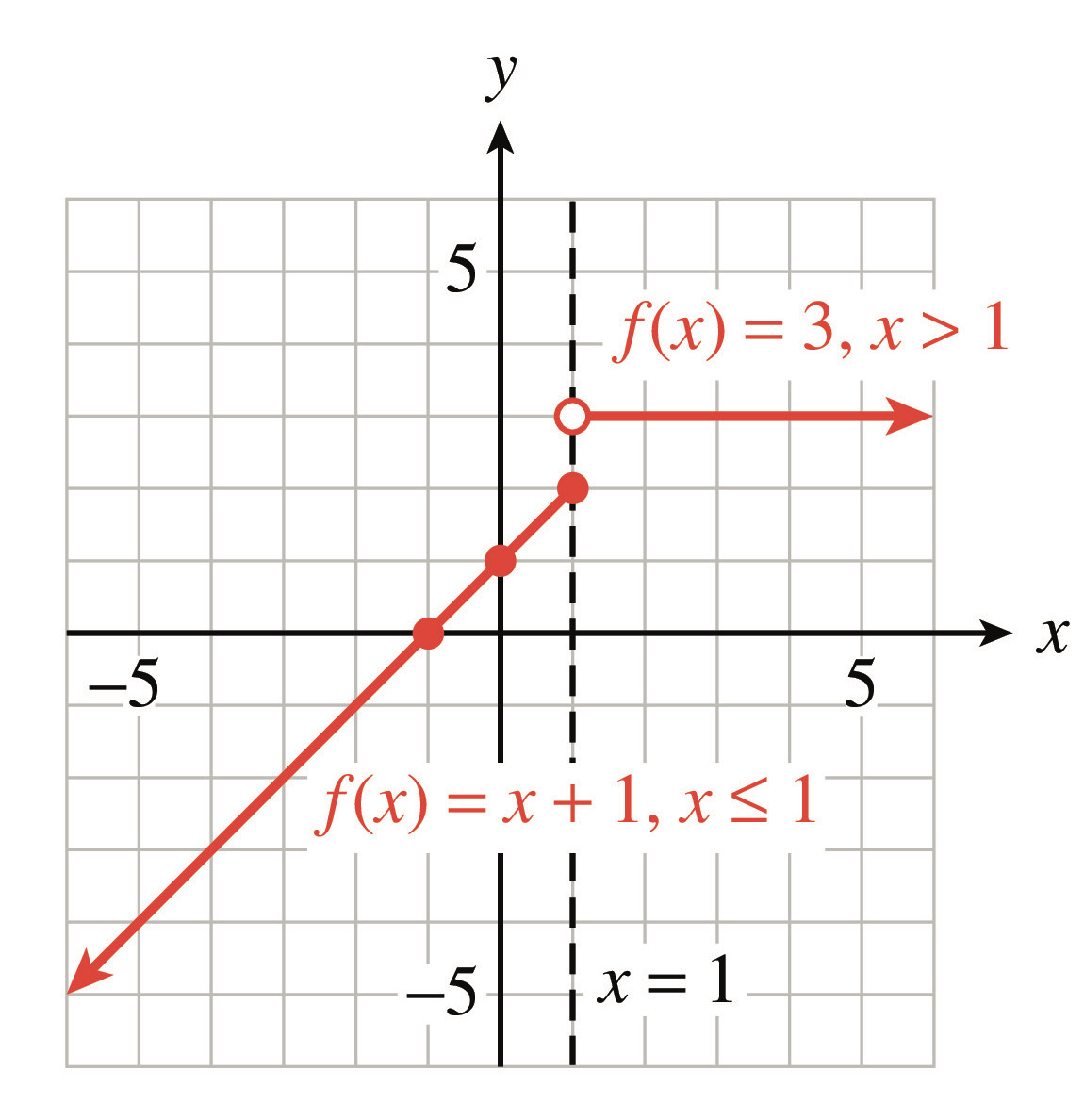

Amber measures herself before going to bed and is 67 inches tall. She measures herself again when she wakes up 8 hours later, and is now 68 inches tall. Let \(h(t)\) be Amber’s height in inches \(t\) hours after the first measurement. Then \(h(0)=67\) and \(h(8)=68\text{.}\)

Do you think there is a time between when Amber goes to bed and when she wakes up that she is 67.5 inches tall?

Since Amber is likely growing continuously (i.e., she did not jump from 67 inches to 68 inches instantly), the Intermediate Value Theorem holds for the height function \(h(t)\text{.}\) The Intermediate Value Theorem states that at some time while Amber slept, she measured 67.5 inches tall.