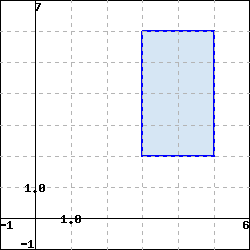

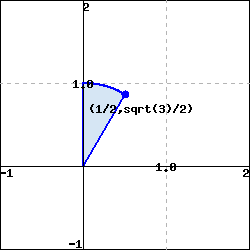

To find the average, we want to take the integral of the function over the region and then divide it by the area of the circle. First, we compute the integral of \(g(x,y) = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}\) over the interior of the circle \(x^2 + (y-1)^2 = 1\text{.}\) We can rewrite our function using the substitution \(r^2=x^2+y^2\) to get \(\sqrt{r^2}=r\text{.}\) Then

\begin{align*}

\int_0^{\pi} \int_0^{2\sin(\theta)} r r\,dr\,d\theta

\amp = \int_0^{\pi} \int_0^{2\sin(\theta)} r^2 \,dr\,d\theta\\

\amp = \int_0^{\pi} \left[ \frac{1}{3}r^3 \right]_0^{2\sin(\theta)}\,d\theta\\

\amp = \int_0^{\pi} \frac{1}{3}(2\sin(\theta))^3 \,d\theta\\

\amp = \frac{8}{3}\int_0^{\pi} \sin^3(\theta) \,d\theta\\

\amp = \frac{8}{3}\int_0^{\pi} \sin(\theta)\sin^2(\theta) \,d\theta\\

\amp = \frac{8}{3}\int_0^{\pi} \sin(\theta)(1-\cos^2(\theta)) \,d\theta\\

\amp = \frac{8}{3}\int_0^{\pi} \sin(\theta)-\sin(\theta)\cos^2(\theta) \,d\theta\\

\amp = \frac{8}{3}\left[ -\cos(\theta)+\frac{1}{3}\cos^3(\theta)\right]_0^{\pi}\\

\amp = \frac{8}{3}\left[1-\frac{1}{3}-(-1 + \frac{1}{3}) \right]\\

\amp = \frac{32}{9}.

\end{align*}

To find the area of the circle, we could compute the integral \(\int_0^{\pi} \int_0^{2\sin(\theta)} r\,dr\,d\theta\text{.}\) However, since our region is just a circle of radius 1, we can also use the formula for area of a circle to get that the area is \(\pi(1)^2=\pi\text{.}\) Then the exact average of \(g\) over the circle is

\begin{equation*}

\frac{\frac{32}{9}}{\pi} = \frac{32}{9\pi}.

\end{equation*}