Solve the initial value problem

\begin{equation*}

y' + y = t^2 + 2t + u_1(t)(t + 1 + \delta_1(t)), y(0) = 0

\end{equation*}

We take the Laplace transformation of both sides. To take the Laplace transformation of \(u_1(t)(t + 1 + \delta_1(t))\text{,}\) we rewrite the factor being multiplied by \(u_1(t)\) replacing \(t\) with \(t+1\text{,}\) giving \(t+2 + \delta_1(t+1) = t + 2 + \delta_0(t+1-1) = t + 2 + \delta_0(t)\text{;}\) take the Laplace of this and multiply by \(e^{-1s}\text{,}\) giving \(e^{-s}(\frac{1}{s^2} + \frac{2}{s} + 1)\text{.}\) We arrive at the equation

\begin{equation*}

sY(s) + Y(s) = \frac{2}{s^3} + \frac{2}{s^2} + e^{-s}(\frac{1}{s^2} + \frac{2}{s} + 1)

\end{equation*}

Therefore,

\begin{equation*}

Y(s) = \frac{2}{s^3(s+1)} + \frac{2}{s^2(s+1)} + e^{-s}(\frac{1}{s^2(s+1)} + \frac{2}{s(s+1)} + \frac{1}{s+1})

\end{equation*}

It looks like we have to do extensive partial fractions, but we don’t; observe that

\begin{equation*}

\frac{2}{s^3(s+1)} + \frac{2}{s^2(s+1)} = \frac{2+2s}{s^3(s+1)} = \frac{2}{s^3}

\end{equation*}

and \(\frac{1}{s^2(s+1)} + \frac{2}{s(s+1)} + \frac{1}{s+1} = \frac{1+2s+s^2}{s^2(s+1)} = \frac{s+1}{s^2}=\frac1s + \frac{1}{s^2}\) So we end up at the equation

\begin{equation*}

Y(s) = \frac{2}{s^3} + e^{-s}(\frac1s + \frac{1}{s^2})

\end{equation*}

We now have to take the inverse Laplace to solve for \(y(t)\text{.}\) The first term on the right gives us \(t^2\text{.}\) The inverse Laplace of \(\frac1s + \frac{1}{s^2}\) is \(1 + t\text{.}\) Since \(\frac1s + \frac{1}{s^2}\) is multiplied by \(e^{-s}\text{,}\) we subtract 1 to the arguments and multiply by \(\delta_1(t)\) to get the inverse Laplace. The final answer is

\begin{equation*}

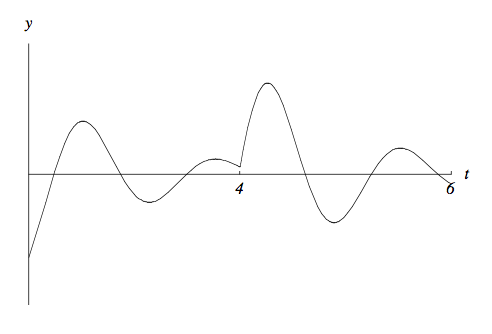

y(t) = t^2 + \delta_0(t)\cdot t

\end{equation*}