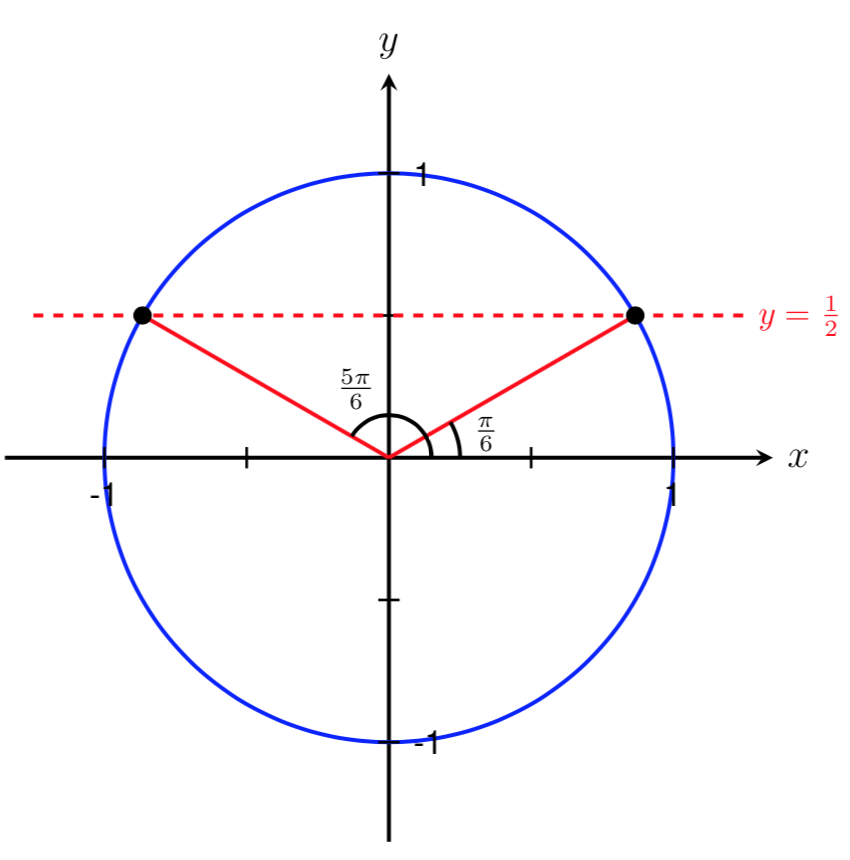

Let's start by drawing a picture and labeling the known information and the angles we are trying to find.

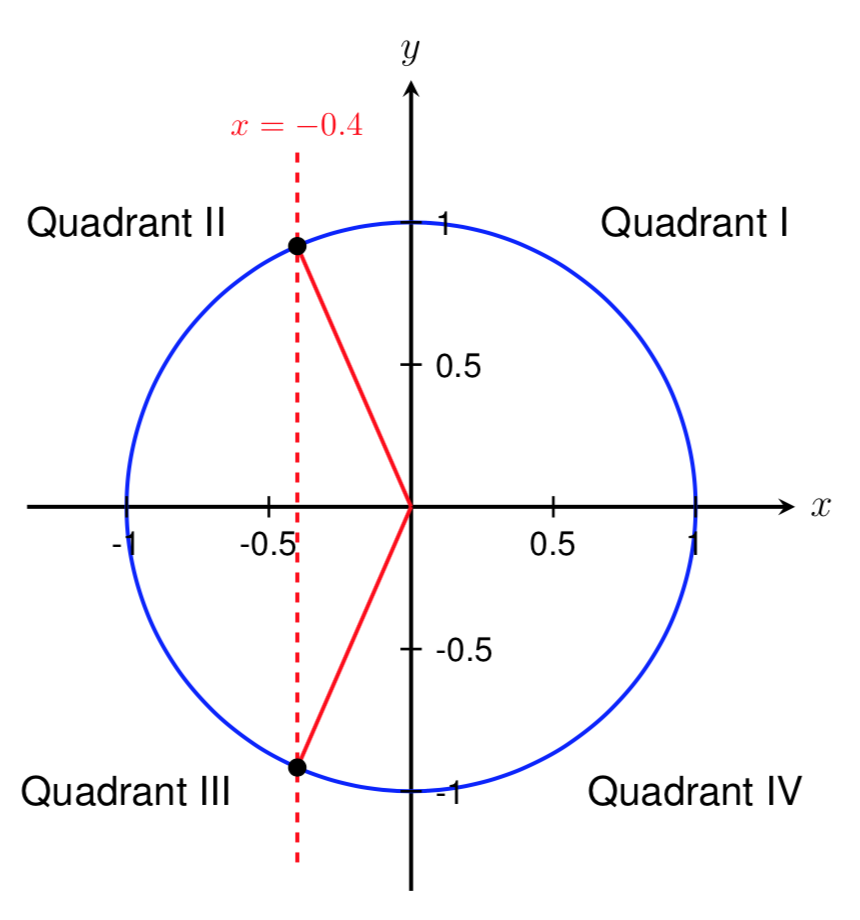

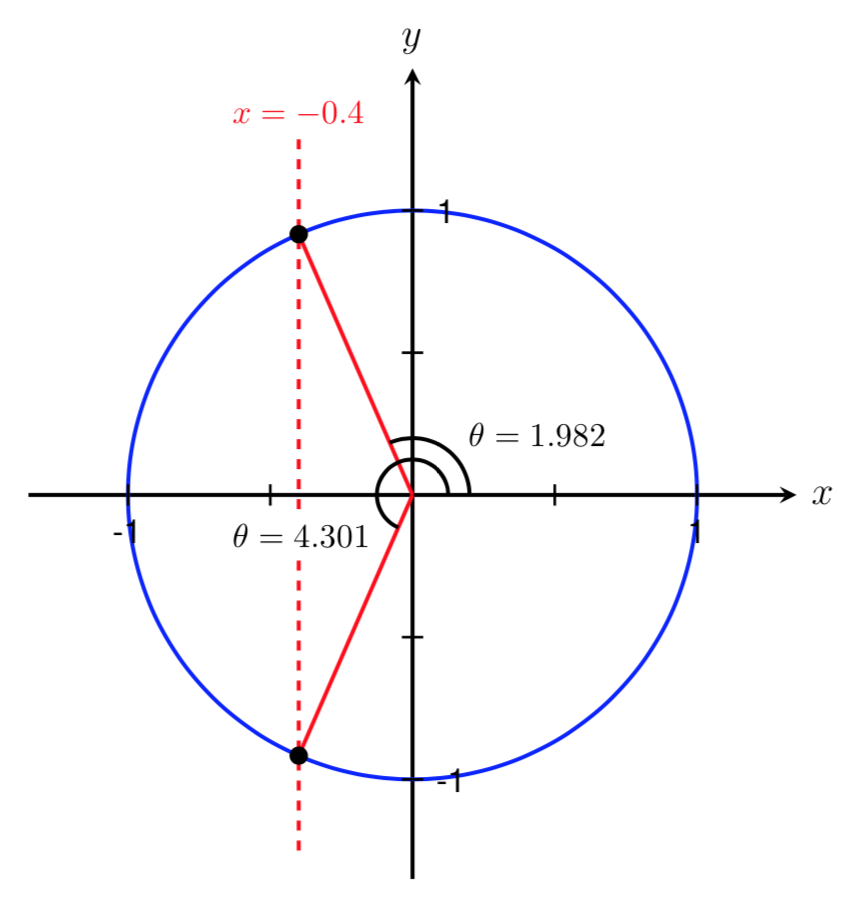

Since we are given a cosine value, we know that we are looking for angles with an \(x\) coordinate of \(-0.4\) on the unit circle. Below is a sketch showing two angles that correspond to \(\cos(\theta) = -0.4\text{.}\) Notice that these two angles lie in Quadrant II and Quadrant III since our cosine value is negative.

Since \(x=-0.4\) does not correspond to a common angle on the unit circle, we need to use a calculator to solve for an approximate value of \(\theta\text{.}\) Applying the inverse cosine function we get that

\begin{equation*}

\theta = \cos^{-1}(-0.4)

\end{equation*}

To evaluate this, we can use our calculator. Since the output of the inverse function is an angle, our calculator will give us an angle in degrees if it is in degree mode or an angle in radians if it is in radian mode.

Here, we need to decide whether to provide our answer in degrees or radians. Since we are given the interval \([0,2\pi]\text{,}\) which is radians, we will provide our answers in radians. Using our calculator in radian mode we get that

\begin{equation*}

\theta \approx 1.982 \text{ radians}

\end{equation*}

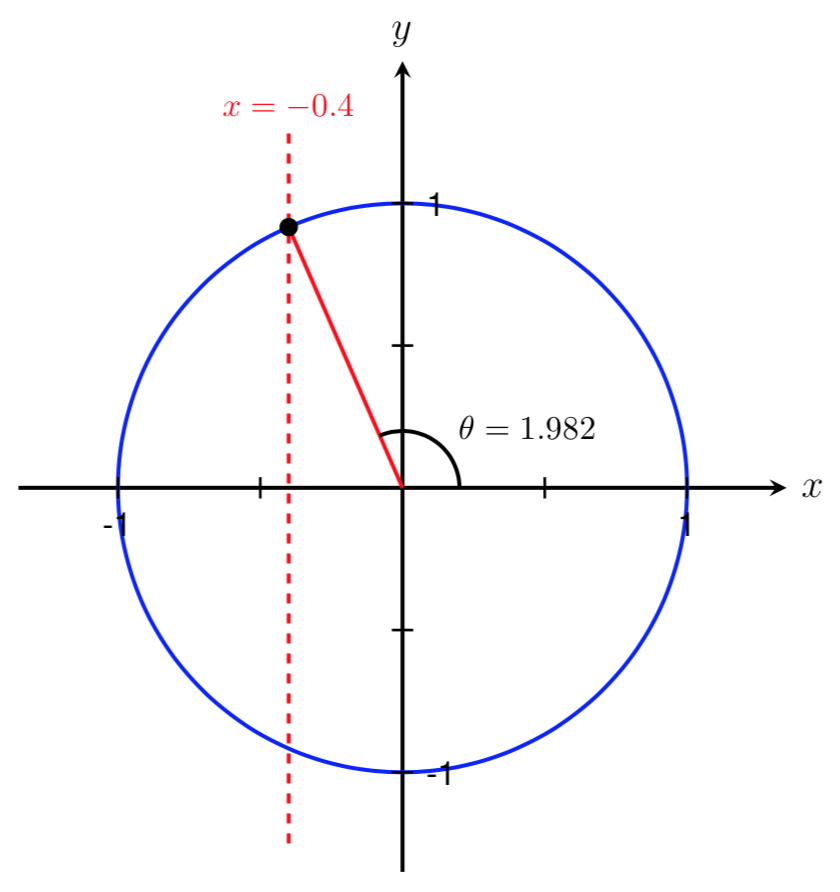

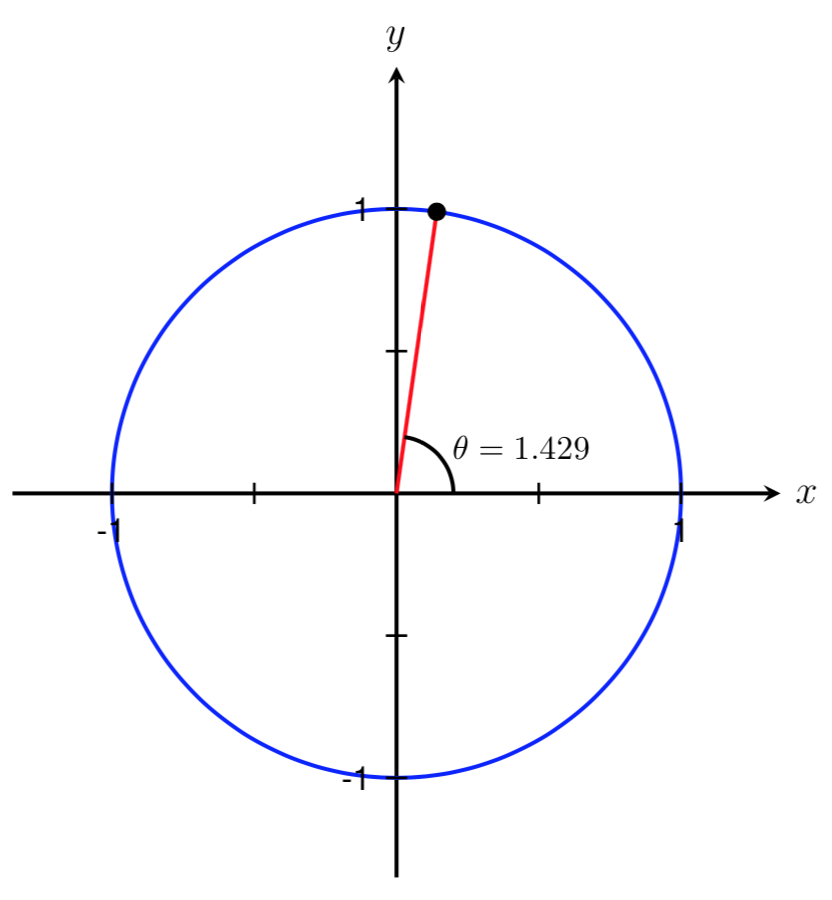

We have now found one angle in the interval \([0,2\pi]\) such that \(\cos(\theta) = -0.4\text{.}\) However, as shown above, \(\theta\) could lie in either Quadrant II or Quadrant III. Since 1.982 is bigger than \(\frac{\pi}{2} \approx 1.571\) and smaller than \(\pi \approx 3.142\text{,}\) we know that \(\theta=1.982\) lies in Quadrant II. Therefore, we have found the angle shown below.

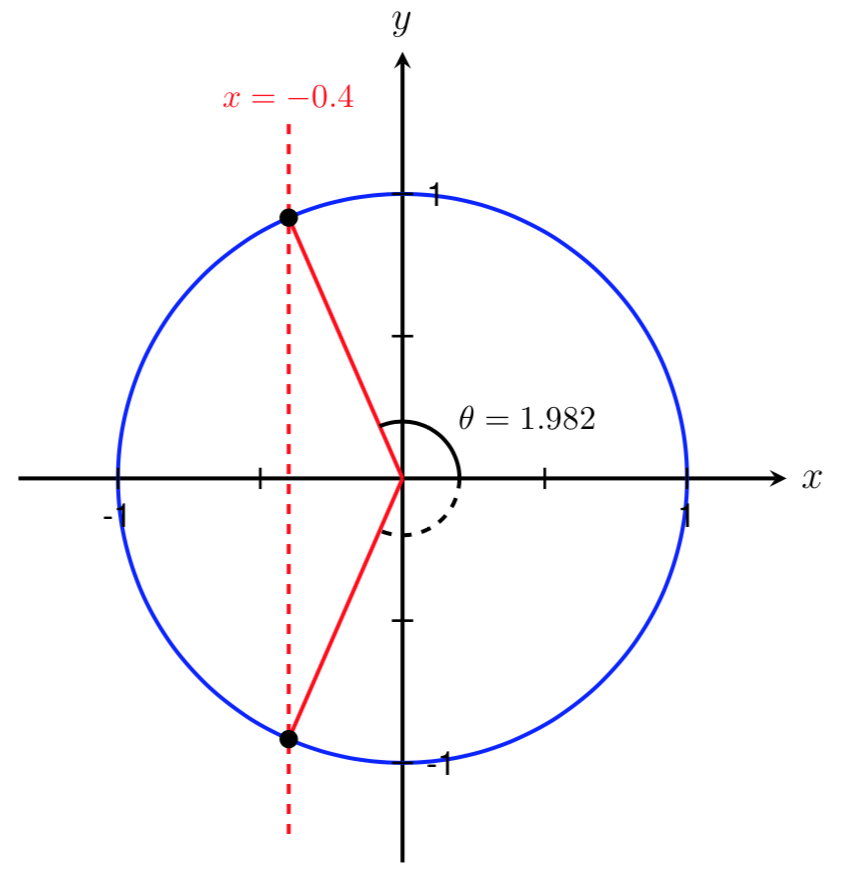

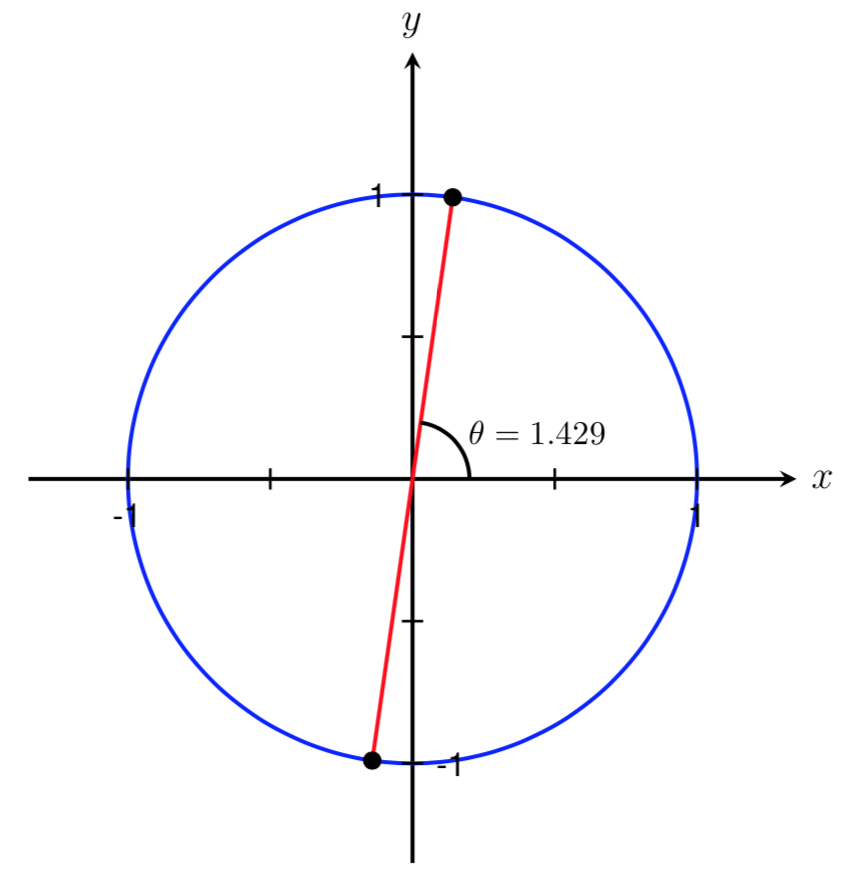

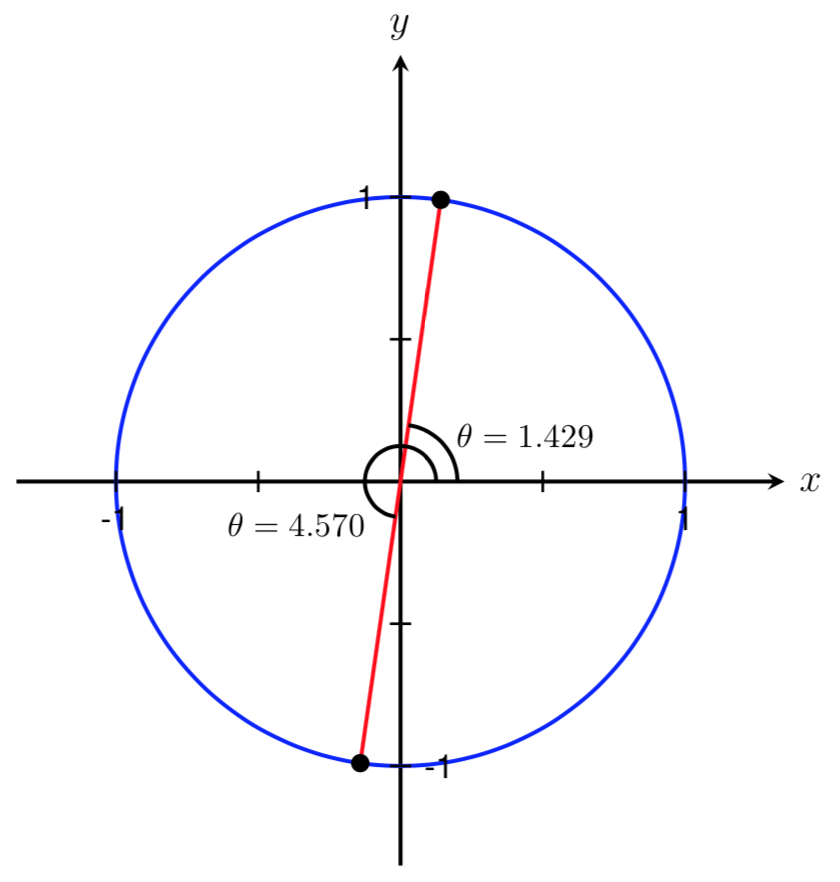

We can now use symmetry to find a second angle in the interval \([0,2\pi]\) such that \(\cos(\theta) = -0.4\text{.}\) We know this angle should be located in Quadrant III. By symmetry, we also know that the two angles shown below are equal.

Therefore, to find the second angle, we can take the first angle we found and subtract it from \(2\pi\text{.}\) This gives us an angle of

\begin{equation*}

\theta \approx 2\pi - 1.982 \approx 4.301 \text{ radians}

\end{equation*}

Thus, the two angles in the interval \([0,2\pi]\) that satisfy \(\cos(\theta) = -0.4\) are

\begin{equation*}

\theta \approx 1.982 \text{ radians} \hspace{.25in} \text{ and } \hspace{.25in} \theta \approx 4.301 \text{ radians}

\end{equation*}

An easy way to check our solutions is to evaluate \(\cos(1.982)\) and \(\cos(4.301)\) on our calculators. If our calculator returns values close to \(-0.4\text{,}\) then we know the angles we have found are correct. Using our calculator (in radian mode), we get

\begin{equation*}

\cos(1.982)=-0.3997 \hspace{.25in} \text{ and } \hspace{.25in} \cos(4.301)=-0.3999

\end{equation*}

Since both of these values are very close and round to -0.4, we can be confident that we have found the two angles in the interval \([0,2\pi]\) that satisfy \(\cos(\theta)=-0.4\text{.}\)